President Donald J. Trump boards Air Force One for his return flight home from Tampa International Airport in Tampa, Florida / Official White House Photo by Joyce N. Boghosian

One thing the United States has always prided itself on is freedom. It identifies as a ‘free country’, the face of the ‘free world’ and the ‘land of the free’. From its immigrant roots to its quest for independence from Britain’s colonial rule, the American experience has been carefully constructed around financial opportunity. The freedom to pursue idealistic financial security has always been as important as the freedom from the cyclical wrath of poverty. This conception of freedom does not stop with the buck either: The First Amendment protects citizens’ sacrosanct freedom of expression, while the Second confers their qualified freedom to hold arms.

For the Republican Party, or ‘The Party of Free Trade’, freedom of contract and limited government are typically held as bedrock constitutional principles. Indeed, to President Hoover, the key to “unparalleled American greatness” was the American choice of “rugged individualism” over European doctrines of paternalism and state socialism. Only, this Administration no longer embodies true American Republicanism.

It is no secret that tensions with China have been simmering since the mounting tariff trade war, cyclical rounds of retaliatory sanctions, the passing of new laws in Hong Kong, military movements near Taiwan’s borders and the outbreak of the Coronavirus. The U.S. Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, demonstrated as such in his July 2020 speech: “If we don’t act now, ultimately [the Chinese Communist Party] will erode our freedoms and subvert the rules-based order that our free societies have worked so hard to build.”

One month later, President Trump signed the Executive Order on “Addressing the Threat Posed by TikTok” giving effect to a commercial blockade on TikTok’s parent company, ByteDance Ltd. Yet it lacked a single reference to freedom; in its stead were multiple references to “national security” and “the economy”. President Trump proceeded to deliver an ultimatum to the Chinese behemoth: sell the U.S. division to an American Big Tech competitor such as Oracle Inc or be ejected from its 330m consumer market. By pulling the levers of forced state capitalism, he demanded the transfer of the algorithm and majority of equity as terms of the asset sale to the American bidder. He also signalled the end of Republican Sino-American enthusiasm championed by his predecessors, from Presidents Nixon to Reagan to Bush. So, what can explain the emergence of this unorthodox, unprincipled and big state Republican Government?

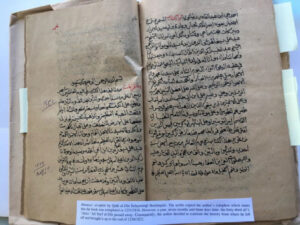

Three competing narratives interplay. The first is officially quoted on the record: ByteDance presents legitimate national security qualms. Its mass collection, processing, extraction and profit from the behavioural surplus of user data pertaining to 80m Americans could be accessed by the Chinese government. Article 7 of China’s National Intelligence Law 2017 specifically imposes a legal obligation on all citizens and organisations to “support, assist and cooperate with the state intelligence work”. Further, Article 16 expands on the liberty of state intelligence staffers to “enter the relevant areas and places that restrict access and ask relevant information”. Where a company consists of three or more members of the Chinese Communist Party, Article 30 of the Constitutions states it must implement the Party’s “principles and policies”.

By establishing a vague relationship between private power and the Chinese government, the U.S. is able to treat both interchangeably. The video-conferencing company Zoom materialised this proximity by obliging requests from the Chinese government to suspend access for users commemorating the Tiananmen Square massacre. Where national security concerns once equated with Iraq’s weapons of mass destructions or Iran’s unconstrained nuclear ambitions, they are now invoked to justify commercial proxy wars. In a marked evolution of foreign policy, economic sanctions and blockades no longer need to primarily target nation states.

The reverse also holds true: qualms with nation states can be scapegoated on to their corporations. The risk of cyber espionage carried out by the Chinese government – a legal justification cited by the Department of Justice – is conflated with the risk of transacting with ByteDance. Similarly, “national security” justified the economic isolation of Chinese telecoms company, Huawei, from the transatlantic 5G landscape. Not only did the U.S. pivot away from Huawei, but it applied extraterritorial pressure to the U.K. to mirror this approach for the foreseeable future.

Problematically, this mutation of foreign policy lacks legitimacy. China’s National Intelligence Law subjects all intelligence to be in “accordance with the law” and give effect to the protection and safeguarding of organisations’ “legitimate rights and interests”. Rather than being unconstrained, their laws hold similar qualifications and caveats to American and English law. Moreover, the Department of Justice lack indicting evidence that prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, ByteDance qualifies as a Communist Party organisation under Article 30. Most importantly, no technical explanation on how the Chinese government can access TikTok’s data stored on U.S. and Singaporean servers is given. By merely relying on the statutory skeleton of Chinese law, President Trump’s Executive Order remains alarmingly hollow by legal standards.

It also begs the elephant-in-the-room: what about Russia? Aside from Trump’s personal admiration for Vladimir Putin, his Administration has taken a different tone to that of China. From refusing to discuss sanctions at meetings with Putin and professing to make “great deals” with Putin, Russia is distinguished from its authoritarian neighbour. Yet Russia should present equal, if not heightened, national security concerns to the U.S.

According to General Sir Nick Carter, the Chief of U.K.’s Armed Forces, Russia was responsible for the 2017 cyberattacks on Ukraine’s banks and government infrastructure. What is more, it continues to engage in sophisticated cybercrime to advance its national interests. The race for a Coronavirus vaccine is illustrative of this interest: The UK’s National Cyber Security Centre implicate the Kremlin’s funding of cyber espionage group APT29, which attempted to steal research from pharmaceuticals and research bodies. Faced with credible evidence of Russia’s threat to national security, the U.S.’s current fixation with ByteDance seems illogical and disingenuous. Curiously, Russian companies who serve U.S. consumers are yet to face this level of state interference.

This leads to the second narrative and competing justification behind big state Republicanism: national economic interest. Rather than national security, American technological supremacy is the true victim and TikTok’s rise to global consciousness crystallises this. Through exhaustive iterations to suit the international audience, TikTok demolishes the ‘copycat’ stereotype painted thus far over Chinese tech. Traditionally, Baidu was characterised as Google’s ‘copy’, Alibaba as Amazon’s, and Didi Chuxing as the Chinese-equivalent of Uber. Only, TikTok’s technology far outshines its American competitors like Instagram, or music-synching apps Dubsmash and [formerly] Vine.

This is more than Beijing’s ‘Zhongguancun’ vying to be the next Silicon Valley. In the words of Alex Karp, the CEO of Silicon Valley firm Palantir, “The country that wins the AI battles of the future will set the international order.” Fittingly, the country whose corporations win the AI battles of the future will wield similar influence, on a scale larger than Google’s. ByteDance’s ability to collect dossiers of user data strengthens the power of its algorithm and paves the path for a strong lead in perception and autonomous AI. Further, the data can be channelled into Chinese behavioural futures markets which offer vast opportunities to profit from targeted advertising and analytics. Against the backdrop of America’s declining superpower status, big state Republicanism is a last-ditch resort to deliver on Trump’s electoral pledge – Make America Great Again.

Yet, the greatest irony in the ByteDance saga is that the U.S. are guilty of what they have always taunted China over – excessive statism. Whereas President Xi’s China has historically championed state subsidies to state-owned enterprise and policies that disadvantage foreign competitors, the U.S. has prided itself on democratic, free-market capitalism. In the own words of Republican President Calvin Coolidge, “the chief business of American people is business.” Trump’s damning ultimatum signals it is high time for the Party and Country to resign this title.

Where there is loss, there can also be gain. Perhaps the Republican Party can reclaim another title – one of self-sufficiency. TikTok’s demise could boil down to a third justification: independence and self-reliance. The geopolitical strategy of decoupling, a subset of deglobalisation, goes one step beyond petty trade wars and actively seeks to detangle economic ties between nations – namely by separating supply chains, discouraging trade and undoing interdependency insofar as possible. The U.S. Department of Commerce’s sanctions on China’s chipmaker, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC), is a clear manifestation of taking back control and reviving the U.S. as the manufacturing centre of the world. Crucially, the Coronavirus pandemic has accelerated this process of decoupling by highlighting the weaknesses of interconnectedness and sweetening the appeal of economic independency.

In this vein, perhaps Trump believes his Party still align with true Republicanism in the name of protecting public interest. After all, American Republicanism pursues an objective conception of public interest which aims to promote virtue in a communitarian sense. This has always been distinguished from the sum of individual interests, meaning the latter must sometimes be compromised in favour of the former. But by triggering a technological cold war and engaging in “technopolitik” – rather than competing to be the better innovator – the land of opportunity can only fall short on its promise to the public.

Ultimately, President Trump’s only memorable legacy will be the jeopardy of future Republicanism.