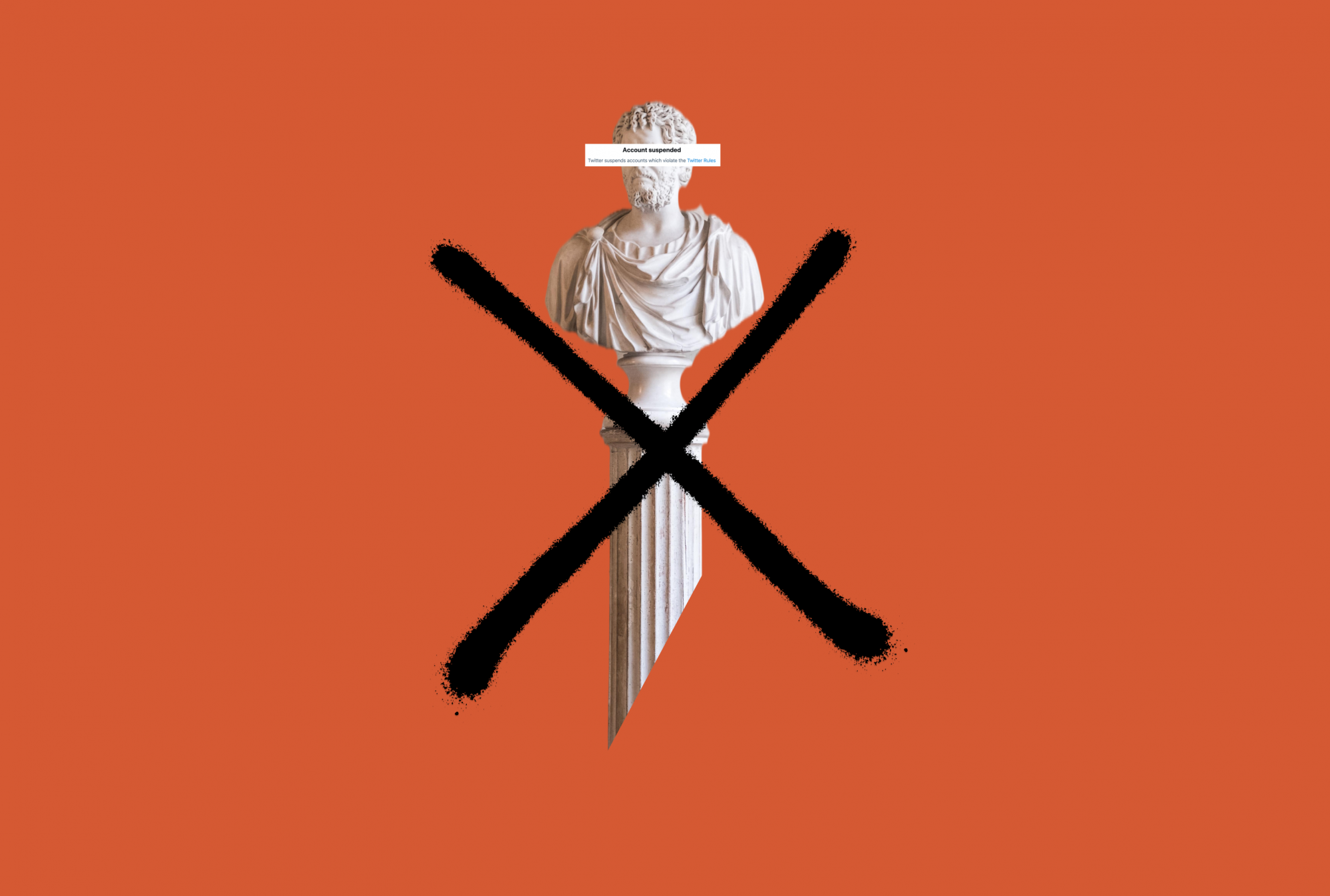

Illustration by Zeyd Anwar; Unsplash

In the aftermath of the social media onslaught of Trump, “content moderation” emerges as Silicon Valley’s new buzz word. And yet, the discussion so far has gravitated among one of three lines: whether platforms were right to ban Trump, wrong to ban Trump, or should have banned Trump years earlier – at the expense of the bigger picture. It is important, on this basis, to ask three basic questions about content moderation: are there different rules for politicians? How consistently are these rules enforced? And finally, what do we want social media to look like?

First, it is important to understand that most social media platforms have a special exception for content that would otherwise violate their rules if it would be in the “public’s interest” to remain online. Generally, the public interest exception is reserved for politicians and those running for office. Platforms also have a “newsworthiness” exception for content that is important but does not originate from politicians, such as recordings of police brutality or videos documenting war crimes. Of course, assessing whether something is in the public’s interest to know or is sufficiently newsworthy to justify relaxing the usual rules is a value judgment. The people setting policy at these platforms may set out to be objective and unbiased, but the reality is this: a small group of people from similar backgrounds decide what their global base of users get to see.

In a world enamoured with democracies, are we too willing to accept content oligarchies? Take, for example, Twitter’s statement that they only invoked the public interest exception “less than five times in 2018″. Setting aside the strangely vague number of “less than five”, it would be interesting to know how many of those exceptions concerned Trump (a topic of perennial interest to American social media platforms), and how many examples came from the myriad of other countries represented on Twitter — in particular, countries where the policy teams are unlikely to have sufficient knowledge about local governance and political issues.

A second concern is that allowing content that breaks the rules just because a politician posted it creates the risk that social media companies become literal “platforms” for political messages. Social media has a tremendous power to disseminate information, foster engagement and catalyse change. While this power can be awe-inspiring, it also emphasises that the content that remains accessible on a platform can have serious implications. Take, for example, the controversy that erupted a few years ago when Facebook was accused of complicity in genocide in Myanmar. It may be in the public’s interest to know that the Myanmar’s military leaders were inciting genocide against the Rohingya people, but how do you balance that fact against the real risk that you are amplifying a call to violence?

This is the same issue platforms had to consider after the Capitol Hill Riots and there are no easy answers. Perhaps it is clearer in cases involving mass atrocities like Myanmar but it is very difficult to predict ahead of time how a politician’s comments on social media will be received and what real-world implications will occur. In the meantime, the baser instincts of politicians are projected to the world when similar sentiments from ordinary people — who typically lack the reach and political support to incite mass actions — would be removed.

There is also the perennial problem that by creating exceptions, you are introducing inconsistency to the rules. This is compounded by the vaguely-worded and discretionary application of exceptions. It is understandable that platforms have had to contend with the fact that real life is messy and that they are unable to draw up a set of air-tight rules that can apply to millions, or even billions of people and achieve the desired result. Countries have been in this regulation game a lot longer than social media platforms and the courts are still full of cases litigating the myriad of exceptions that exist to any law.

Further, the lack of transparency in their decision-making will not be held accountable anywhere but in the court of public opinion. A politician will not really be able to predict ahead of time whether their comments will meet that public interest threshold, just as a citizen journalist risking their life in a war zone has no idea if the content they post will be newsworthy enough or whether it will be discarded as too graphic. It should also be noted that just because platforms have publicly shared rules and their exceptions, does not mean they will always play by their rulebook.

Take, for example, YouTube’s decision to remove videos featuring the radical preacher Anwar al-Awlaki from its platform, after al-Awlaki increasingly became notorious for his connections to violent attacks like the Fort Hood shooting and the attempted murder of British MP Stephen Timms. YouTube removed many of his sermons that had been on the site for long periods of time, including ones that did not appear to violate the terms and conditions. The particular merits of that decision can be debated, but the point remains: platforms sometimes follow their own rules and sometimes they don’t.

When the Trump banning happened, many people proclaimed that platforms, which used to protect free speech, were now violating the right to free expression. It is worth remembering that there is no inherent “free speech” quality in the DNA of social media platforms. They can be heavily moderated (or censored) and often reflect whatever values are politically expedient or even enable business in a particular jurisdiction. Of course, they rely on user-generated-content so there is always an interest in more speech (“the tweets must flow” as Twitter once proclaimed), but rest assured that social media can also be used to further state’s authoritarian objectives through censorship and surveillance.

Every few months, a new controversy over social media erupts. It might be the mass violation of privacy, electoral manipulation, terrorist content, censorship of female bodies, or hate speech, but these scandals appear with disturbing regularity. Concerned citizens then play conversational Whac-A-Mole, discussing these discrete problems without answering the real question that lies at the heart of these debates: what do we want social media to look like? We have two choices. A social media platform can be a curated, sanitised version of the world where civil discourse is required and community values are encouraged. Or it can be an unvarnished reflection of the world, with all of the attendant ugliness and authentic outrage that entails. Both visions have their merits, and most platforms try to strike a balance between these two poles, but this conflict lies at the heart of social media. Whether we are discussing banning Trump or the public interest exception more broadly, what we are really asking is this: what is the purpose of social media? Start from there, and we may have a shot at figuring out what to do next.