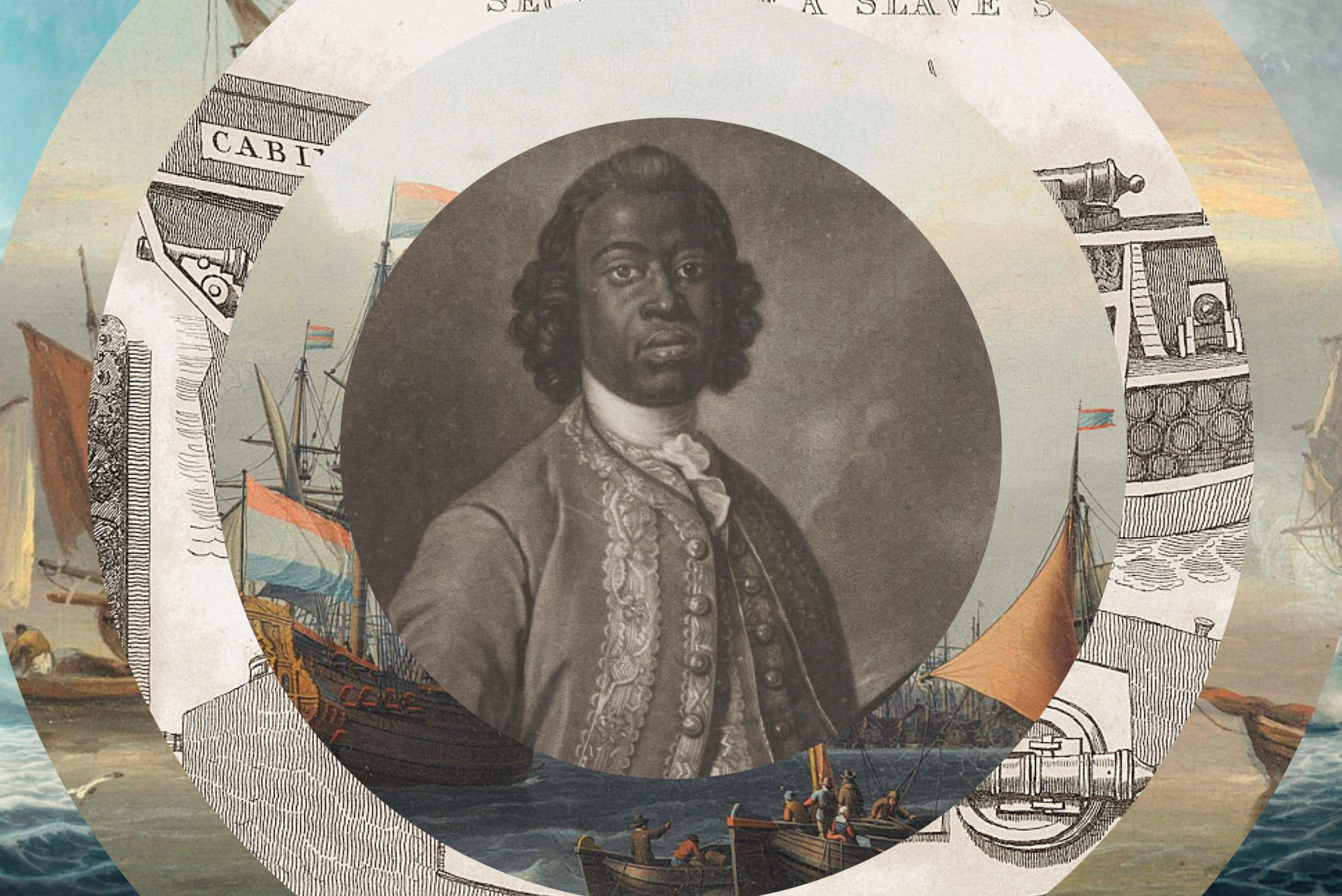

Illustration by Zeyd Anwar; New Politic; National Portrait Gallery; Christies

This article is part of Project Empire, an editorial series designed to explore the history of the British Empire. See the full collection here »

The entrance door to the upper circle and gallery was shut. The rest of the doors had shutters pulled all the way down. I stood in between the middle pillars of the closed theatre, remarking on how out of place it looked. It was the late hours of a Wednesday in the middle of September. The streets were brewing with an eclectic crowd, echoes of youthful laughter stuck to the air, lingering for minutes afterwards until they morphed into a type of kinetic energy that bounced off the bustling city-goers.

Nobody seemed to take much notice of the closed Theatre Royal. Looking up, I looked for signs that betrayed the age of the city’s oldest theatre still in use. Two-hundred and seventy-two years ago, on the first Wednesday of February 1749, a Black man well known as William Sessarakoo sat in the corner of the upper gallery with his close companion (who still remains to be identified, according to sources). They had both just received a loud standing ovation and had returned the audience’s admiration with a graceful bow. On stage, the actors started to play out the latest rendition of the wildly popular play written by Aphra Behn, the Tragedy of Oroonoko.

The romantic tragedy tells the harrowing tale of Oroonoko, an African prince, who was sold into slavery by the betrayal of his own captain, separated from his lover, Imoinda and doomed to a Shakespearean death. Scenes of the physical and emotional abuse suffered at the hands of slave-masters played across the stage and burned into Sessarakoo’s memories. By the end of the fourth act, Sessarakoo’s vision had been shrouded by his own tears, his body so overcome with visceral grief that he could not stomach any more.

His dramatic departure from the theatre was no surprise. His companion remained, weeping throughout the rest of the performance until the audience joined in their tears and smattering applause. The tragedy of Oroonoko paralleled William Sessarakoo’s own life story as the son of an African slave-trading caboceer — the equivalent of a prince or king — who was forcibly sold into bondage in 1748. After emancipation, with the help of the Royal African Company, Sessarakoo was slowly integrated into the British aristocracy and celebrated as both a British icon and a living representation of African nobility.

His story became the subject of drama, poetry and biographies, his image printed and sold on the streets of London and adored by the British press. Eventually he returned back to Annamaboe, the sleepy fishing town in what is modern-day Ghana, with more material wealth than he had arrived and continued the legacy of his father’s slave-trading enterprise.

And yet for all his 18th century fame, Sessarakoo’s story has drifted from British consciousness. Somehow, when we recount our history with slavery, we show collective amnesia of the African prince-turned-slave. Nor was he the only one who experienced this: many Africans were born free, rich and of high status in their countries and died in bondage. That a slave trader’s son could fall victim to the transatlantic slave trade was one of the many twisted ironies of empire — and was gradually erased from British history.

The young prince, or Cupid as he was referred to, was born on the Gold Coast in Annamaboe. located in modern-day Ghana. It was an indigenous African town that grew to be a hub of the transatlantic slave trade upon the arrival of Dutch traders in 1638. It eventually exported 10 percent of all enslaved Africans who were shipped out of Africa.

The trading town was effectively run by Sessarakoo’s father: the rich and powerful Eno Baisie Kurentsi; one of the most influential traders on the West African coast. He acquired his influence through a combination of strategic alliances, including his marriage to the daughter of the king of Akwamu; a marriage which later birthed William Ansah Sessarakoo. Armed with men at his disposal and political support from neighbours, Kurentsi became the godfather of the Gold Coast. European slave traders learned they could not do business without his blessing, and competed among themselves to earn his good favour.

One courting offer came from the French traders. Vying for a monopoly over the slave and gold trades in Annamaboe since 1730, the French were keen to out-manoeuvre the British traders and routinely offered Kurentsi lavish gifts of textiles and brandy. They offered to educate his illegitimate son, Bassi, in Paris and treat him as royalty. Kurentsi was a proud man but shrewd at recognising opportunities where they arose. He eagerly accepted the offer and sent his son packing to Europe, who was subsequently embraced with open arms, adorned in decadent French clothing and introduced to the King Louis XV. British traders grew wary of their neighbours’ schmoozing and upped the ante, matching the French offer for Kurentsi’s second (and reportedly favourite) son, William.

Although only a teenager when he left Annamboe, Sessarakoo was sophisticated beyond his years. His mannerisms, air of grace and charming personality preceded him. Kurentsi proudly credited these personal traits to his son’s maternal royal lineage from one of the “principal persons in the country.” He entrusted no other than the Englishman Patrick Dwyer, suspected captain of the Lively of Liverpool, to take his son and a companion on what was a challenging voyage to Britain in the year of 1744. Kurentsi bid farewell to his son — and his days as a free man.

The captain had other plans. Long before the ship arrived on the shores of Britain, he sold the teenage prince to a slave trader in Barbados as a bargaining tool to receive owed debts from Kurentsi. It was a simple transaction, one where the buyer immediately accepted Sessarakoo as a rightful slave. The captain’s political manoeuvre worked, too; he offered Kurentsi his son’s liberty in exchange for paying off the further remaining debts. Only, by the time Kurentsi could avail the offer, the captain died — leaving any knowledge of Sessarakoo’s whereabouts in darkness and in indefinite bondage.

Little is known about Sessarakoo’s lived experience as a slave. In the contemporaneous account of his kidnap, The Royal African, he is said to have carried out his slave duties in a manner true to his character; without “sullenness and obstinacy.” Despite his state of bondage, Sessarakoo proved to be a noble, heroic slave. Fortunately, the account reports, Sessarakoo was also blessed with a kind Barbados slave master who he described as a “Gentleman of distinguished character… with much Humanity”.

By contrast, other black slaves — who did not have royal status — did not receive these affections. His interactions with them were met with “rough usage”: while he was fundamentally unfit for slavery, Sessarakoo believed they were boorish, “brutish”, “wretched” and “inherently enslaveable”. Inspired fictionalised accounts of his bondage, such as Dodd’s poems “The African Prince” and “Zara’s Answer”, reimagined his ordeal with extra flair. One account added romance to Sessarakoo’s ideal, suggesting he and his star-crossed lover were separated in different plantations. Another account narrated Sessarakoo as a victim of the cruel, bullying slaves who mocked his suffering. Notably, both fictional accounts show his misery as a product of his interaction with other slaves rather than the institution of slavery itself.

The idea of a justified slave took off in the West. When news broke that Kurentsi’s son was enslaved, Kurentsi refused to part any more favours to the British traders until he could guarantee his son’s freedom. Concerned they would lose their claim to an Annamaboe monopoly, the Royal African Company quickly deployed its men to find and free Sessarakoo.

The Company was seen as an “ambassador of British values”, denouncing the moral deficiencies of the separate, mercenary slave traders who had traded in Sessarakoo’s freedom. But their main contention was not the trade of slaves: it was the trade of royal slaves. The mercenaries were admonished for their inability to recognise the social — and royal — status of the African prince. Their presumption that all Black people were ordained to be slaves irrespective of social class was considered vulgar, and ultimately a vice of the growing slave market.

Kurentsi’s deal, it turned out, worked. The newly emancipated Sessarakoo arrived in London not long after around December 1748, this time with a companion and assurances from his father. It is not clear the chief reason for his return: some sources suggested he wanted to further his father’s business relations with the British, while other suggest he pursued his education. He was received by a “numerous court at St. James’s”, adorned in rich English clothing, placed under the protection of the Earl of Halifax and even introduced to King George II. From the outset of his arrival, Sessarakoo was intent on being accepted by the English aristocracy. The Royal African attested to this claim, “his plainly shews, that good Sense is the Companion of all Complexions, and that the Brain in black Heads was made for the same Purpose as in white, whatever some People may imagine.” Unlike the mercenary traders, they understood the currency of hierarchy.

The English consensus was that the privileged aristocrat was too noble and pure for his fate and did not deserve slavery. But, due to his natural nobility and good breeding, he was still considered a model slave. This narrative played into the hands of the proslavery movement. Unlike the masses of poor Black Africans enslaved in the British colonies, royal Africans — much like the European nobility — were on par with free Englishmen.

In Ryan Hanley’s words, “sentimentalised and sensationalised” stories about wrongly-enslaved royal Africans hardened attitudes that common Black slaves had “natural” differences from the African elite. The contemporary adaptations of his story make sure to tell a story of individual, rather than collective and systematic, suffering. The Oronooko audience’s emotional outburst in Covent Garden was likewise an isolated one, one that did not translate to the transatlantic slave trade. Rather, the English’s acceptance of William Sessarakoo confirmed that in the 18th century racial hierarchies were still secondary to the natural class order.

It was not until later versions of play were adapted that Sessarakoo’s story was noticed by the growing abolitionists in Britain. Yet Sessarakoo was not too concerned with any revolution against slavery. He and his companion returned to Annamaboe aboard the HMS Surprize on 14 August 1750, with more material wealth from his stay in Britain than he was set to inherit from his wealthy caboceer father. Once he arrived home safely, it was business as usual with the British and French traders. Whereas he previously played a functional part of his father’s slave-trading business, the former slave now freely dealt with the slave-traders. His ordeal even strengthened the establishment of the Royal African Company: if the slave trade was left to the free-market mercenary traders, it risked descending into every slaver’s worst nightmare — a rogue, decentralised and free-for-all ‘unethical’ business.

The tragedy of Sessarakoo is one of forgotten slavehood. His story sheds light on the paradox of slavery: that victimisation as a slave was not enough to question the deep-rooted institution of slavery. The African prince was able to overlook his lived reality as a slave in place of the opportunities as a slave-trader. Loyalty to class over racial solidarity was not just a dominant theme in Britain — like much of the Empire, it eventually pervaded sleepy, small African towns such as Annamaboe.