This article is part of Project Empire, an editorial series designed to explore the history of the British Empire. See the full collection here »

I doubt many of us would feel comfortable putting up a statue with the following quote inscribed below:

I contend that we are the finest race in the world and that the more of the world we inhabit the better it is for the human race. Just fancy those parts that are at present inhabited by the most despicable specimens of human beings what an alteration there would be if they were brought under Anglo-Saxon influence…

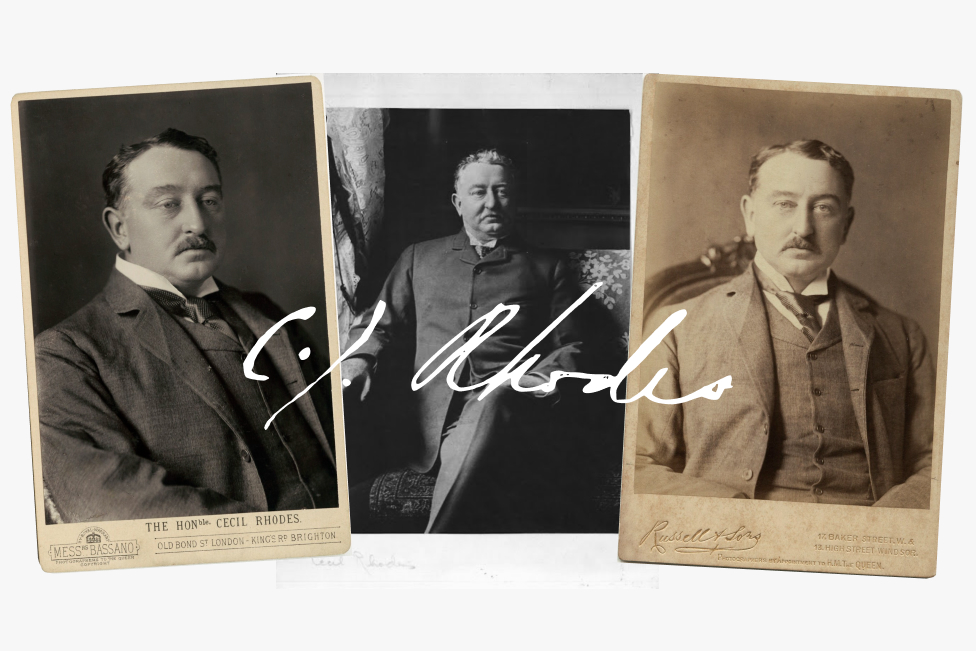

But this would be the most fitting way to honour Cecil Rhodes, whose statue at Oriel College, Oxford has become the focus of so much attention. There is no better example of the racism, exploitation and violence of the British empire than Rhodes. By the time he moved to Southern Africa as a teenager in the 1870s, Britain and other European nations had subjugated Africa through slavery and violence. Rhodes gorged on the opportunities afforded to him through Britain’s colonial rule by making his fortune in diamond mining. DeBeers, the multibillion dollar diamond company, was founded by Rhodes himself. It now stands as the perfect example of how the West continues to impoverish the African continent by stripping it of its resources and generating obscene profits.

Rhodes became so wealthy and influential that he rose politically and created his own kingdom called Rhodesia, in what is now modern-day Zimbabwe. He annexed the territory with violence and even possessed his own private police force, named the British South Africa Police (BSAP). His instructions to his officers during the Matabele Rebellion was to “do the most harm you can to the natives around you…to kill all you can.” Rhodes may never have personally enslaved or murdered another, but his private police were responsible for, at the very least, the deaths of tens of thousands and the displacement of millions. In the racist logic that justified the slavery of Africans, Rhodes once declared that “it is our duty as a Government to remove these poor children [he was referring to adults] from this life of sloth and laziness, and to give them some gentle stimulus to come forth and find out the dignity of labour.” In 1894, Rhodes later introduced land “reforms” that restricted Africans to certain land, arguing that in a “native area…there should be no white men in its midst. I hold that the native should be apart from white men and not mixed up with them.” Indeed, Rhodes’s playground of Rhodesia even laid the blueprint for Apartheid in South Africa.

Rhodes is undoubtedly one of the most despicable men in history. Yet he is still venerated in Britain and South Africa as a benevolent philanthropist. The fact Rhodes possessed enough wealth to endow the Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford University — which still supports international students — is not something to uphold nor celebrate. Rhodes only possessed such wealth because of his brutal exploitation of South Africa.

The complaints of those demanding Rhodes must fall should be blindingly obvious. And yet, a result of the purposeful amnesia of the horrors of the British empire, such demands are now treated as outrageous. I went through two decades of British (so-called) education and never once heard the words British empire uttered in a classroom. This is a remarkable feat, since the British empire was the largest to exist in history and is the single most important influence in the creation of modern Britain. It was not always like this. In the early twentieth century, Empire was celebrated in schools throughout Britain, with annual Empire Day and tales of colonial adventures. But now, with the migration of millions of those descended from the victims of colonialism, revelling in the glories of Britannia has been rendered uncomfortable. Britain has decided to present an edited version of its own history, where the tens of millions of enslaved, starved and murdered Black and Brown bodies are as erased from the collective memory as they were from the face of the earth.

Rhodes is not unique in his horrible history. Neither is his sanitised place in the public consciousness. He is a product of empire and his statue is a perfect example of the disturbing way we misunderstand what Britain exactly is.

***

The most important aspect concerning the debate over statues in Britain is that it is not about history, but very much about the present. Statues depict a person’s influence or power, or act as testaments to a version of history that we want to remember. Giant, imposing statues do not exist to teach its onlookers, but to enforce a message from the past, one that is meant to shape the future. Rhodes’s statue is a reminder that the architects of Oxford University, and indeed Western knowledge, were steeped in the very racism that allowed Britain to conquer the world. The past is now, and we venerate slave traders and colonial exploiters so we can ignore the dark side of how we came to be where we are. Pulling down every single Rhodes statue would not erase him from the history books, nor his wider influence on the world. If anything, the debate about his statue has ensured that his name will continue to be remembered.

The battle over statues is about which stories we should elevate and what messages from the past we want to shape the present. If we are committed to an anti-racist future, then memorials to Rhodes and his ilk must be consigned to the dustbin of history. We do not need blue plaques for “context”, and we should drop the “man of his times” defence. There were millions of people who disagreed with Rhodes at the time, not least the millions of Africans subjected to his oppression. If we are serious about framing history in an inclusive way, we too must abandon any plans to put such statues in museums. Edward Colston’s statue should have been left at the bottom of the Bristol harbour, and joined by several other such monuments to empire.

The uncomfortable truth, however, is that British society is not committed to an anti-racist future. In the aftermath of last year’s Black Lives Matter summer, it became crystal clear that despite decries against racist violence, there is little appetite for the systemic change needed to address racial inequality. The logic of empire — that Black and Brown life is disposable to enrich the lives of White people — is just as alive and well today as it ever was.

Indeed, the underdevelopment of Africa was essential to the riches we see in the present, and it is no coincidence it remains the poorest continent today. African labour provided the wealth necessary for the industrial revolution, while Africa’s bounty of natural resources provided the raw materials. In this regard, Rhodes was a pioneer, arguing during his time that “Africa is still lying ready for us. It is our duty to take it.” And take it Britain and the rest of Europe did. The modern world, with all of its technical innovations, would not have been possible without the material necessary stolen from African soil. So Rhodes was a conquering hero. He was part of a cadre of fascists who brutally ushered in Western progress. The problem is not that he was a violent racist, but that we are now living off the fruits of his violent racism.

If we are to be honest, the problem with Rhodes’s statue at Oxford University is not its presence, but the fact that it is not large or prominent enough. Christopher Columbus, who hacked, burned and roasted the path for European progress in the Atlantic is given his proper due in the Americas. Not only is the seat of the US capital in a district bearing his name, but the most powerful nation in the world (one that Columbus never set foot in) also has a public holiday for his birthday. The fact he sparked the largest genocide in human history did not stop Columbia being named after him. Frankly, I would prefer it if Britain fully embraced its fascist founding fathers, rather than cobbling together transparent and weak defences for maintaining its monuments. At least then we could have an honest debate.

Once we realise that the most important figures in building Britain today have their hands soaked in blood, it might encourage us to begin to understand the scope of change necessary to deliver racial justice. So, of course Rhodes should fall. But it will only be meaningful if he is one domino that sets off a chain, one that pulls down the racist political and economic system — that he was so important in building — crashing to the ground.