On a late summer’s afternoon of 15 August 1945, King George VI stood up to make his annual King’s speech at the Opening of Parliament in Westminster, London. “In accordance with the promises already made to my Indian peoples,” he declared, “my Government will do their utmost to promote, in conjunction with the leaders of Indian opinion, the early realisation of full self-government in India.” The significance of the moment could not be understated: two centuries of British colonial rule in India would come to an end. In the days and months following, the date of independence was accelerated 10 months earlier from an anticipated date in June 1948 to August 1947. Two years from the exact date of King George’s speech, India had realised independence and the state of Pakistan was born – leaving the South Asian continent forever altered.

The imperial decisions, metrics and calculations taken in those preceding months changed the course of history for nearly half of a billion South Asians. What made it worse was the British Orientalist view of India as one homogenous lump of land, which informed their short-sightedness to the nuances within and between the people of India. Misguided electorate policies sharpened religious differences in India and fuelled intolerance. Uninformed and unrepresentative maps were drawn by Britons with no knowledge of India. Impatient civil servants neglected their administrative jobs as they watched their reign near end. The infrastructure of British India slowly crumbled while the British retreated with indifference as to what it meant to be ‘Hindu’, ‘Muslim’ and ‘Sikh’, or what it took to set up two stable independent states.

***

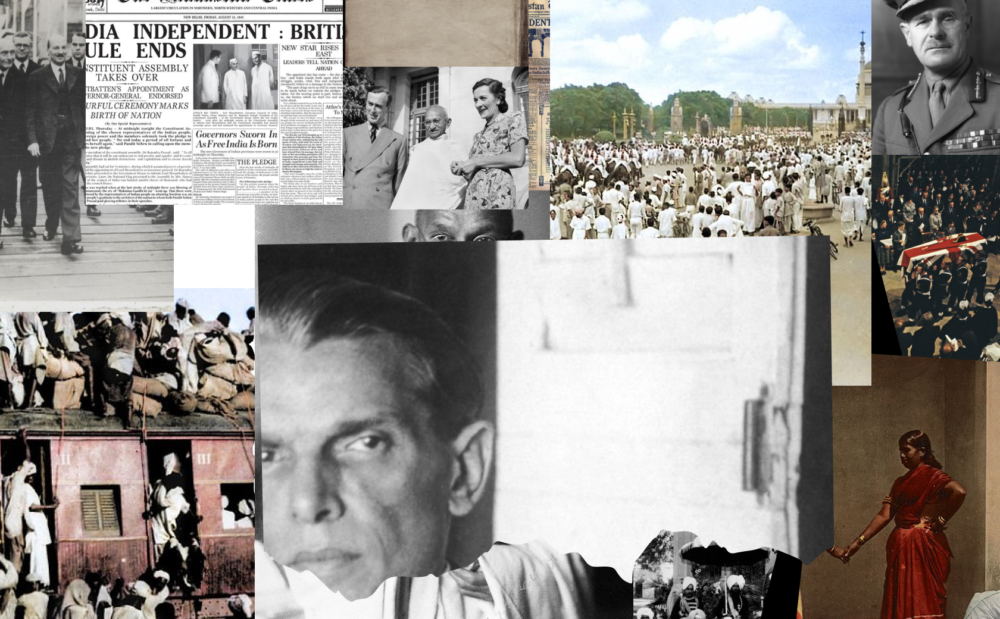

To some historians, World War II, independence and Partition were all “mutually intertwined”. It wasn’t clear where or when wartime politics ended and the politics of independence began, writes Yasmin Khan, the author of The Great Partition. In 1939, Britain folded 2.5 million Indian soldiers into its war without prior consultation with India’s Congress, resulting in over 24,000 soldiers dead and 64,000 wounded. In the midst of the ensuing national protests and Congressional opposition to the British Government, an opportunity arose for the All-India Muslim League to offer allyship to the British in exchange for political favours. By March 1940, the Muslim League passed a resolution calling for the creation of separate states to accommodate Indian Muslims (what came to be known as the “two nations” theory). The leader of the Muslim League and Governor-General of Pakistan to be, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, made it clear that the right of sovereign Muslim States must be substantially composed of the British Indian Provinces now regarded as Muslim (e.g., in the north-west; Sind, Baluchistan, the North-West Frontier Province and the Punjab, and in the north-east, Assam and Bengal). The right to self-determination and separate sovereignty was to be exercised by their Muslim residents alone.

Jinnah addresses the Muslim League session at Patna, 1938

Jinnah could thus not agree to any provisional Government, or any alliance between the Hindus and Muslims, to achieve independence before the Muslim claim to a separate state was validated. Mahatma Gandhi, by contrast, wanted self-determination for Muslims within a united India. In Lord Archibald Wavell’s words, “Jinnah wants Pakistan first and independence afterwards, while Gandhi wants independence first with some kind of self-determination for Muslims to be granted by a provisional Government which would be predominantly Hindu.” And yet, “Jinnah was arguing for something which he has not worked out fully, and Gandhi was putting forward counter proposals in which he did not really believe at all.”

Over in Westminster, there was increasing support for India to reach some sort of settlement between the political leaders: namely, the Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru; Jinnah; Gandhi; and the representative of the Sikhs, Baldev Singh. In a memorandum by the Lord Privy Seal Clement Attlee, dated February 1942, he acknowledged this, “The fact we are now accepting Chinese aid in our war against the Axis Powers… as an equal and of Chinese as fellow fighters for civilisation against barbarism makes the Indian ask why he, too, cannot be master in his own house.” He referenced the “large contribution in blood and tears and sweat” made by Indians and deliberated between appointing representatives of high standing already in India to negotiate a settlement, or bringing representative Indians to London to flesh out negotiations with the Cabinet. Ultimately choosing the first, he concluded that “Lord Durham saved Canada to the British Empire. We need a man to do in India what Durham did in Canada”.

Sure enough, one month later the British Government sent Sir Stafford Cripps on his first mission to India to offer independence after the war in exchange for cooperation. The Cripps mission did not take long to fail as both the Indian Congress and Muslim League rejected initial proposals of independence to a strong, united India. Pressure continued to mount from the other side of the Atlantic to secure strategic security interests. In a telegram from the U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt, to his trusted advisor Harry Hopkins in April 1942, he expressed “the feeling is held universally that the deadlock has been due to the British Government’s unwillingness to concede the right of self-government to the Indians,” he continued, “should the current negotiations be allowed to collapse… and should India subsequently be invaded successfully by Japan… it would be hard to over-estimate the prejudicial reaction on American public opinion”.

It was not until the Labour Party’s landslide victory in the summer of 1945, and Churchill’s departure from Downing Street, did Britain renew negotiation efforts in India. Recuperating the costs of war, the new Labour Prime Minister Clement Attlee decided the over-extended empire was a luxury Britain could no longer afford. He soon dispatched a Cabinet Mission to India in early 1946 with the intention of going back to the leaders to attain India’s freedom “as speedily and fully as possible”. Attlee was particularly keen, on paper, to set up the machinery for India to decide what form of government would replace the existing colonial regime of diarchy (which left defence, budgeting and foreign affairs squarely in British hands). It was also now abundantly clear that the Muslim League had convinced the British that the Pakistan issue was to be dealt with. In the words of Penderel Moon, a senior government secretary and insider in Delhi, “… the Pakistan issue has got to be faced fairly and squarely. There is no longer the slightest change of dodging it.” As Britain entered the last stages of decolonisation, however, the political machinery put in place rang hollow.

***

Some of this machinery came in the form of general elections. Elections were staggered from December 1945 to March 1946 and around 10% of India’s general population were eligible voters. Unusually, these elections carried undue weight: voters weren’t just deciding the temporary make up of their next government, they were casting a vote on the intangible and arbitrary concepts of Indian Freedom and Pakistan. In Yasmin Khan’s words, “It was a peculiar mixture of the lofty and the mundane; it was a nation-making referendum with international and permanent implications about state formation.”

By mid-1946, however, the Cabinet Mission yet again failed to forge a settlement and a waft of anti-Europeanism descended on the streets of major Indian cities. Both Congress and, eventually, the Muslim League rejected the proposed constitutional scheme for India, which suggested a loose federation of Indian states. Dejected, British authorities began to lose their lustre of “moral sanction” and hastened their retreat from the administrative duties of the Raj. Unwilling to spend more money on public services, district officers, policemen, magistrates and investigation and intelligence officers suffered in quality and numbers, ultimately weakening the backbone of the Indian state and ripening it for instability and social disorder. The British administration knew the state was crumbling.

A new type of rage fuelled the riots and the street fights that broke out thereafter. As soon as the Cabinet Mission plan failed, scuffles and stabbings intensified in frequency. While riots were not new to the Hindu, Sikh or Muslim communities, this time the violence “seemed stranger and less manageable”. In July 1946, rioting and non-discriminate stabbing attacks in the Gujarati city of Ahmedabad had become common-place. Bands of political activists broke out in city streets, processions clashed and men fought pitched battles, throwing stones and brickbats. In August 1946, the Muslim League passed a second resolution calling for direct action to “get rid of the present British slavery and the contemplated future Caste-Hindu domination.” In an expression of deep resentment of the British, the League announced they would renounce the titles conferred by an “alien Government”. The subsequent Great Calcutta Killing left some 4,000 people dead and a further 100,000 homeless – marking a watershed, point-of-no-return moment for the future of the Indian subcontinent.

One British governor captured the British sentiment in the midst of unravelling chaos, “I told him that there was a whirlwind coming which some- body would have to reap. It probably wouldn’t be me, for I would be gone.” Others, such as the British district magistrate, A.P. Hume, “represented the worst of the British in India.” Right until his final days in India, writes Khan, against the backdrop of the mayhem that was unfolding, Hume went on camps, shooting parties and summer holidays in the Himalayan hills. His closest encounter with violence was when telephone reports came into the magistrate’s bungalow of stabbings, interrupting his dinner and causing him to carry out late night tours of the city. In a sorrowful letter to his family back home, Hume lamented “it is most painful and depressing to assist in the passing of a great empire.”

Quickly realising the situation in India was spiralling out of hand on Britain’s watch, Attlee sent a new viceroy to salvage the process of decolonisation. Lord Louis Mountbatten arrived in Delhi in March 1947 and swiftly announced the time pressure to reach an agreement. Unlike his predecessor, Lord Wavell, who had spent his childhood in India, Mountbatten had no such hesitancies to take steps that could have bloody consequences. According to Khan, within a month of Mountbatten’s arrival, he was on board with the plan for partition and had started to think that Pakistan was inevitable – he had arrived on the scene too late to alter the course of events.

Jinnah and Gandhi arguing in 1939

In May 1947, Nehru visited Mountbatten at Simla, where Mountbatten showed him the revised set of proposals for partition that had already been approved by the British Government. To Nehru’s dismay, the proposals marked a sharp departure from previous notions of a strong Indian Union – the recurring theme of all negotiations thus far. In other words, the Muslim League’s previous vetoes of a united India had been successful: Mountbatten had listened. Nehru, on the other hand, had a visceral reaction. Fearing the ‘Balkanisation of India’, Nehru lambasted the plans presented by Mountbatten, who hurriedly revised plans to meet these expectations. Critically, the border had to be decided against the clock. The lines drawn would ultimately draw within five weeks would determine the livelihoods, homes, families, and future of the ties between the Hindu, Sikh and Muslim communities.

On 30 June, British lawyer and judge Cyril Radcliffe formed the Bengal Boundary Commission and the Punjab Boundary Commission to take on the gargantuan task. Radcliffe was tasked as the man of the hour, despite never having been to India before. The Boundary Commissions worked with outdated censuses of around six years, and none reflected the ebb and flow of refugees who had already migrated during the ongoing violence. As Independence Day drew nearer, Khan notes, the response to the threat of an unknown borderline became desperate, “the telephone at the Governor of Punjab’s house was ringing incessantly around the clock with callers desperate to convey their position. Depositions and appeals came in the form of telegraphs and petitions, letters and phone calls”.

On 3 June 1947, Prime Minister Attlee made an announcement to the House of Commons, which reverberated across all 1.8 million square miles of India. From Calcutta to Bombay, Quetta to Madras, the Indian people stopped to hear the future of their nation. The British Government, in agreement with the Indian political parties, had at last come to a workable agreement – all that was required was the final sign off from Congress and the Muslim League. The hotly disputed areas of the Chittagong Hill Tracts and the Punjab were yet to be decided, and a referendum remained to be held in the North-West Frontier Province as to which Constituent Assembly they would join: Pakistan’s, or India’s. The rest, however, was considered fair game. Britain relinquished its control of India on the 15 August 1947 and the results of the Boundary Commissions were announced on 16 August 1947. The new borders that sliced the key provinces of Punjab and the Bengal in two were approved on 17 August 1947.

While 12 million migrants subsequently uprooted their lives and crossed the freshly drawn borders, almost 1 million died in the ensuing violence over the implications of the separation. For Sikhs, their calls for a separate Sikh state had fallen on deaf ears and their communal interests were “sacrificed on the altar of a broader constitutional settlement.” The regiments of the Indian army were also dismembered, writes Khan, “Soldiers were combed out and mechanically divided according to their religious hue; blocs of Muslim soldiers were hastily packed off to Pakistan while non-Muslim soldiers were dispatched in the opposite direction”.

In London, on the other hand, politicians washed their hands of responsibility and association with the futures of India and Pakistan. Foreseeing the widespread violence which erupted the country, it was ultimately “perceived as their problem” even though the newly formed governments were not yet functional. By the time they were functional, they were fundamentally “understaffed, under-resourced and sometimes operating from under canvas.” After 90 years of official British diarchal rule in India, the British Government rushed the Indian Independence Act through Parliament to “unhook” itself from India in less than six weeks. Cyril Radcliffe burned his notes before leaving India, never to return to the territories he had architected.