Illustration by Zeyd Anwar; New Politic

This article is part of Project Empire, an editorial series designed to explore the history of the British Empire. See the full collection here »

“Since I have been here I have often wondered how English people can go out into the West Indies and act in such a beastly manner. But when they go to the West Indies, they forget God and all feeling of shame, since they can see and do such things. They tie up slaves like hogs — more them up like cattle, and they lick them so as hogs, or cattle or horses never were flogged…” Mary Prince, 1831.

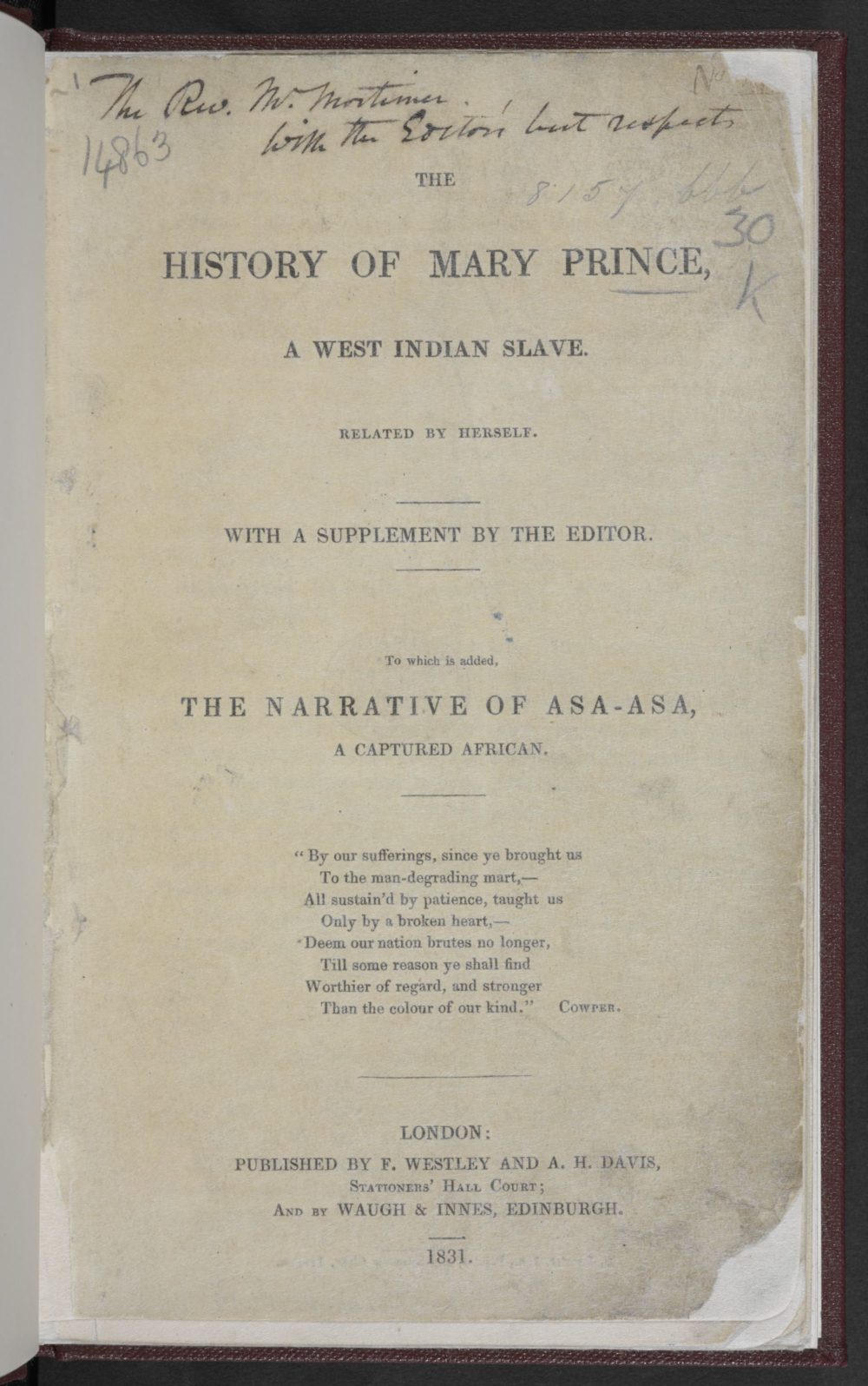

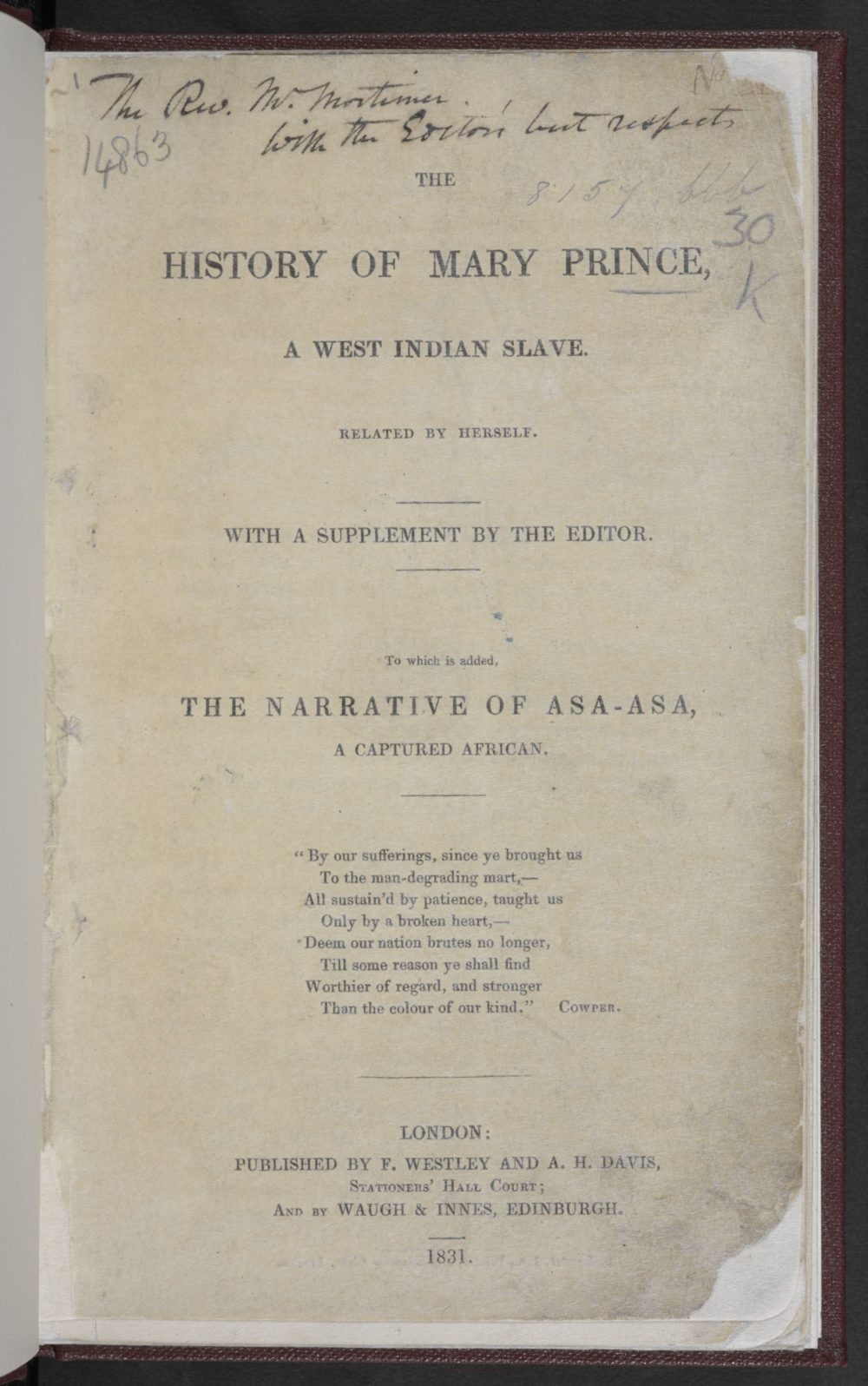

In the story of the abolition of slavery in Britain and its colonies, we are told about the campaigns of men like William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson, as well as former slaves such as Ottobah Cugoana and Olaudah Equiano. Yet the history of the abolitionist movement in Britain leaves out another transformative figure: Mary Prince. From her time as a slave in the West Indies to her travels in England in 1828, Mary Prince became the first Black British woman to escape slavery and publish a record of her experiences as a slave. When The History of Mary Prince: A West Indian Slave was published by the British Anti-Slavery Society in London and Edinburgh in 1831, it attracted a large readership for addressing not only the harsh reality of slave life, but the extent to which slavery corrupted the morals of the white planter class. The History of Mary Prince was reprinted twice by the end of 1831 and served as a corollary to many narratives of former slaves sponsored by the Anti-Slavery Society.

Prince’s narrative contributed to the debate on abolition in a manner much different from the religious arguments used by her contemporaries: it provided a raw, authentic and emotional account of her life as a slave, striking at the injustice of slavery.

The History of Mary Prince: A West Indian Slave is a symbol of tenacity and resilience. Yet it is also an important record to the history of early Black writing, offering a glimpse into the lives of the enslaved men, women and children whose stories can no longer be traced.

“…few people in England know what slavery is. I have been a slave — I have felt what a slave feels, and I know what a slave knows; and I would have all the good people in England know it too, that they may break our chains and set us free.”

Prince was born in 1788 to enslaved parents on a farm belonging to Charles Myners in Brackish Pond, Devonshire parish in Bermuda, a self-governing British colony. Prince’s mother worked as a housekeeper for Myners, while her father — owned by a white man named David Trimmingham — worked as a carpenter. As an infant, Prince and her mother were purchased by a Captain Darrel, who gave Prince to his granddaughter, Betsey Williams. Williams and Prince became playmates, and Prince recalled this period of her life as “happy”, since she was “…too young to understand rightly my condition as a slave, and too thoughtless and full of spirits to look forward to the days of soil and sorrow.” As a child, Prince noted that she “…was made quite a pet of by Miss Betsey, and loved her very much. She used to lead me about by the hand, and call me her little nigger.”

Prince’s joyous childhood ended at the age of twelve, when she and two of her younger sisters were sold by Captain Darrel, then a widower, to raise money for his new wedding. Prince recalled her mother’s grief — and that of the other enslaved people on the estate — as the three girls were taken and sold like sheep or cattle to the highest bidder. “…strange men…examined and handled me…” Mary wrote, “and talked about my shape and size…as if I could no more understand their meaning than the dumb beasts.” The sorrow that followed was too much for Prince to bear. “I then saw my sisters led forth, and sold to different owners: so that we had not the sad satisfaction of being partners in bondage. When the sale was over, my mother hugged and kissed us, mourned over us, begging us to keep up a good heart, and do our duty to our new masters. It was a sad parting; one went one way, one another, and how our poor mammy went home with nothing….my heart was quite broken with grief…‘Oh my mother! My mother!’ I kept saying to myself. ‘Oh, my mammy and my sisters…shall I never see you again!’”

Once purchased, Prince’s new owners set her to work long hours. As soon as Prince entered the house, she was forced to care for the owners’ children, wash their clothes and tend to their animals. “When I went in, I stood up crying in a corner. Mrs. I — came and took off my hat…and said in a rough voice, ‘You are not come here to stand up in corners and cry, you are come here to work.’ She then put a child into my arms, and, as tired as I was, I was forced instantly to take up my old occupation of a nurse.”

Prince quickly learned that no matter how hard she worked, her owners were rarely satisfied and punished her with severe beatings. “…there was scarcely any punishment more dreadful than the blows received on my face and head from her hard heavy first. [Mrs. I] was a fearful woman, and a savage mistress to her slaves,” Prince wrote. On one occasion, Prince was beaten heavily for breaking a glass jar. “I could not help the accident…I ran crying to my mistress, ‘O mistress, the jar has come in two.’ ‘You have broken it, have you?’ she replied; ‘come directly here to me.’ I came trembling: she stripped and flogged me long and severely with the cow skin; as long as she had strength to use the lash, for she did not give over till she was quite tired.”

As her master came home that night, he too inflicted some punishments. “After abusing me with every ill name he could think of…and giving me several heavy blows with his hand, he said, ‘I shall come home to-morrow morning at twelve, on purpose to give you a round hundred.’ He kept his word — Oh sad for me! I cannot easily forget it.” Prince explained how “he tied me up upon a ladder, and gave me a hundred lashes with his own hand, and master Benjy stood by to count them for him. When he licked me for some time he sat down to take his breath; then after resting, he beat me again and again, until he was quite wearied, and so hot (for the weather was very sultry), that he sank back in his chair, almost like to faint.” Prince crawled away from the whipping, and explained how she was “in a dreadful state — my body all blood and bruises, and I could not help moaning piteously. The other slaves, when they saw me, shook their heads and said, ‘Poor child! Poor child!’ — I lay there till the morning, careless of what might happen, for life was very weak in me, and I wished more than ever to die.”

First Edition cover of The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian Slave: Related by Herself / British Library

Prince ran away back to her mother, who later hid her in a nearby cave. When her father learned of this, he was compelled to return his daughter to the slave master. He pleaded with the slave master not to beat her so severely, but this was to no avail. “When we got home, my poor father said to Capt. I—, ‘Sir…the treatment she has received is enough to break her heart. The sight of her wounds has nearly broke mine — I entreat you, for the love of God, to forgive her for running away, and that you will be a kind master to her in future.” No matter their age, the enslaved had no legal recourse, no voice and no choice in what happened to them or their families. As Prince once wrote, “Mothers [and fathers] could only weep and mourn over their children, they could not save them from cruel masters — from the whip, the rope, and the cow skin.”

The History of Mary Prince included discussions of other enslaved people that Mary knew and worked with over the years, and who suffered other similar emotional and physical abuse at the hands of their owners. “In telling my own sorrows, I cannot pass by those of my fellow slaves — for when I think of my own griefs, I remember theirs.” Enslaved men were punished with tortious beatings, imprisoned without food or water, and were forced to keep working despite old age. Young, enslaved boys were punished and whipped endlessly, “whether the children were behaving well or ill.” Prince recalled another slave, named Hetty, who was beaten so bad during her pregnancy that she died:

“One of the cows had dragged the rope away from the stake to which Hetty had fastened it, and got loose. My master flew into a terrible passion, and ordered the poor creature to be stripped quite naked, notwithstanding her pregnancy, and to be tied up to a tree in the yard. He then flogged her as hard as he could lick, both with the whip and cow-skin, till she was all over streaming with blood. He rested, and then beat her again and again. Her shrieks were terrible. The consequence was that poor Hetty was brought to bed before her time, and was delivered after severe labour of a dead child. She appeared to recover after her confinement, so far that she was repeatedly flogged by both master and mistress afterwards; but her former strength never returned to her. Ere long her body and limbs swelled to a great size; and she lay on a mat in the kitchen, till the water burst out of her body and she died. All the slaves said that death was a good thing for poor Hetty; but I cried very much for her death. The manner of it filled me with horror. I could not bear to think about it; yet it was always present to my mind for many a day.”

The poor diets and dire living conditions under which Prince and other slaves lived and worked under led to physical infirmities and other severe illnesses. Such was the case when Prince went to work in the salt mines on Turks Island. Prince and others worked for long hours, standing up to their knees in brine under the hot sun. “Our feet and legs, standing in the salt water for so many hours soon became full of dreadful boils, which eat down in some cases to the very bone, afflicting the suffers with great torment,” Prince recalled. Yet the life of a slave was resilience: they worked all day and night, even when they could barely walk on their sore feet.

Prince repeatedly accused many of the white planters who owned her of heartless, moral corruption in their dealings with enslaved Black people. She exposed Captain Darrel as a lewd, licentious brute: “He had an ugly fashion of stripping himself quite naked and ordering me then to wash him. I would not come, my eyes were so full of shame. He would then come and beat me…I [finally] told him I would not live longer with him, for he was a very indecent man — very spiteful and too indecent with no shame for his servants, no shame for his own flesh.” It is unclear what personal services Captain Darrel demanded of Prince, since her narrative — edited and published by the abolitionist Thomas Pringle — had to conform to patterns of Christian morality and female decorum, alongside a 19th century reading audience. One thing, nevertheless, was clear: Prince was subjected to great torment throughout her years as a slave.

Prince travelled to London in 1828 while enslaved to Mr and Mrs John Wood. The Woods purchased Prince 15 years earlier from Captain Darrel. On several occasions, Prince asked the Woods that she be sold to another owner so that she may eventually pay for her own freedom, but each time a buyer approached John Wood, he refused to sell Prince. These refusals angered Prince and fed her determination to win her own freedom. With the Woods’s permission, she earned extra money by working in other households, and by selling produce at a profit she had bought on board ships when the Woods were away from home. Prince also joined the Moravian Church in Antigua, where she learned to read the bible, to pray and to participate in religious services.

It was here where Prince met a free Black man, Daniel James, whom she later married despite protests from the Woods. “When Mr. Wood heard of my marriage, he flew into a great rage, and sent for Daniel…Mr. Wood asked him who gave him the right to marry a slave of his? My husband said, “Sir, I am a free man, and thought I had a right to choose a wife; but if I had known Molly was not allowed to have a husband, I should not have asked her to marry me,” Prince wrote. It was Mrs. Wood, however, who was more vexed about Prince’s marriage, and she stirred up her husband to flog Prince “dreadfully with the horsewhip.” James tried to purchase Mary, but his offers were refused. “I had not much happiness in my marriage, owing to my being a slave. It made my husband sad to see me ill-treated,” Mary recalled.

Prince and her husband James agreed that she should travel with the Woods to London. The Woods’s daughter had attended boarding school in London and the time had come to enrol their younger son, too. Prince was to travel with the Woods to care for their son. Prince, however, had also fallen ill with rheumatism and other debilitating illnesses. By travelling to London, Prince believed that she would “probably get cured of my rheumatism, and should return with my master and mistress, quite well, to my husband.” Her husband was willing for her to go to London “for he had heard that my master would set me free, — and I also had hoped that this might prove true; but it was all a false report.”

The trip across the Atlantic made Prince’s condition worse. Her swollen limbs and aching body meant she could barely walk. Prince complained, yet the Woods compelled her to wash their clothes. “Mr. and Mrs. Wood, when they heard this, rose up in a passion against me. They opened the door and bade me get out. But I was a stranger, and did not know one door in the street from another, and was unwilling to go away.” After multiple quarrels, Prince took them at their word: she left their home and received assistance from the British Anti-Slavery Society, and it was there she found work as a maid in the home of Thomas Pringle, then the secretary and editor of the Anti-Slavery Reporter. At Mary’s request, Pringle agreed to help her publish the narrative of her life.

Although a short narrative of approximately 40 pages, The History of Mary Prince caused a stir in London. Several of Prince’s former owners, including the Woods, brought a lawsuit against Pringle for libel. Pro-slavery advocates railed against the text as untrue and against Prince as a disreputable character. Pringle, along with Prince, consulted with lawyers and showed written evidence (a letter from John Wood himself) showing her owners refused to pay her for work in his household and refused to grant her manumission. The Anti-Slavery Committee attempted to reach a compromise with John Wood, but to no success. The Committee considered “bringing the case under the notice of Parliament.” Alarmed at the prospect of having Prince’s case against him publicly discussed in the House of Commons, John Wood left London with his family for the West Indies. Prince was unable to return to her husband and family in Antigua, for the fear of re-enslavement and of John Wood’s reprisals.

There is little evidence that shows what happened to Prince after her narrative was published. It is unlikely that she was ever able to return to her home in the West Indies. In statements appended to the second and third editions of her book, we learn Prince gradually lost her eyesight and that many readers inquired about “the existence of marks of severe punishment on Mary’s body” as proof of what Prince said happened to her during her enslavement. A small group of British women, among them Susanna Strickland — who first transcribed Prince’s story — examined Prince’s body and wrote a detailed description of large scars on her back and other parts of her body. “Mary affirms, that all these scars were occasioned by the various cruel punishments she has mentioned or referred to in her narrative,” Strickland wrote. Prince’s scars were a script, her body a text of her sufferings she experienced while enslaved.