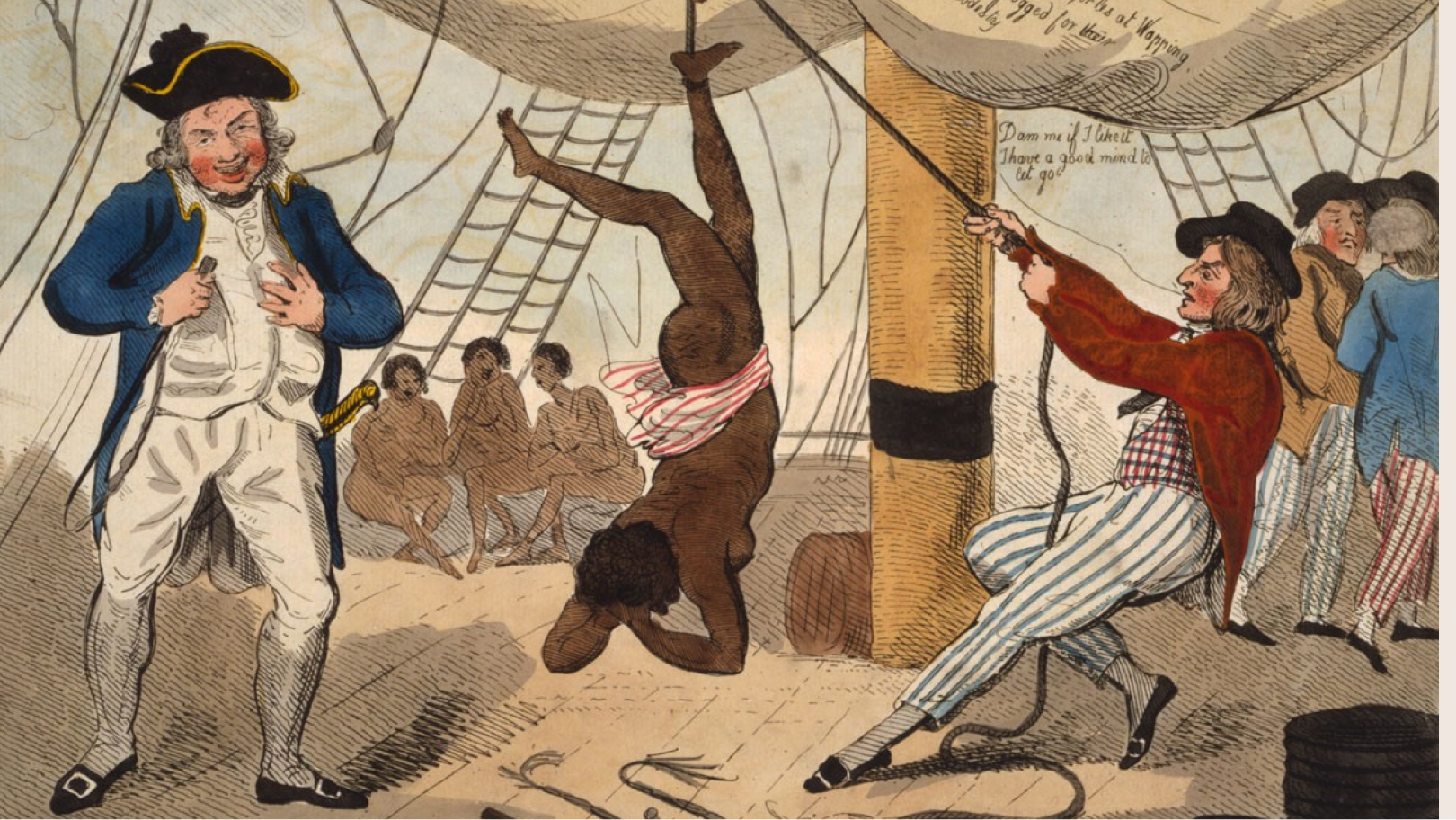

It is no surprise that the whip is synonymous with New World slavery: its continual crack remained an audible threat to enslaved workers to keep at their work, reminding them that their lives and bodies were not their own, and that they should maintain (outwardly at least) a demeanour of dutiful subordination to their overlords. The whip was a cruel and effective instrument of torture — part of the brutal technology that kept the productive machine of plantation America at work. Nowhere was this more obvious than on the islands of the Caribbean. By the middle of the 18th century, these were the most valuable parts of the British empire, and the large island of Jamaica, with its huge sugar plantations and brutal slave regime, was the jewel in the imperial crown.

As elsewhere in the Americas, the right of masters in Jamaica to punish slaves was enshrined in law, and the violence that sustained slavery went far beyond whipping. Punishments could include amputation, disfiguring, branding and more. Slaves could also be put to death — a penalty most often enforced during the aftermath of rebellions. And they were rarely killed quickly. The torturous executions meted out to those who led uprisings or who were accused of collaborating in rebellious plots provide some of the most lurid examples of human cruelty on record.

But physical abuse alone could not keep the lucrative plantations of the British Caribbean productive. It is impossible to get large groups of people to perform sustained labour effectively and consistently for years on end simply through doling out pain and raw terror. Even the most brutal of slaveholders were therefore compelled to develop a sophisticated system of management that exploited the most human aspirations and fears of the people they dominated.

Creating divisions between slaves was essential to this. Enslaved people outnumbered free whites in the British Caribbean. In Jamaica the ratio was higher than 10 to one, and on some big plantations it was about 100 to one. Managers therefore needed to divide slaves in order to rule over them. The slave trade from Africa provided them with one opportunity. As a manager of several large Jamaican sugar estates remarked in 1804, it was a general policy to ‘have the Negroes on an estate a mixture of nations so as to balance one set against another, to be sure of having two-thirds join the whites’ (in the event of an uprising). The theory behind this was that enslaved people from one African ‘nation’ would refuse to join rebellions plotted by those from others, or by creole (locally born) slaves, choosing instead to serve their white masters in the hope of rewards for loyal service.

Privileging some enslaved people above others was another effective means of sowing discord. Slaveholders encouraged complex social hierarchies on the plantations that amounted to something like a system of ‘class’. At the top of plantation slave communities in the sugar colonies of the Caribbean were skilled men, trained up at the behest of white managers to become sugar boilers, blacksmiths, carpenters, coopers, masons and drivers. Such men were, in general, materially better-off than field slaves (most of whom were women), and they tended to live longer.

The most important members of this enslaved elite were the drivers, responsible for enforcing discipline and work routines among the other enslaved workers. These men were essential to effective plantation management — a conduit for orders and, sometimes, for negotiations between white overseers and the massed ranks of field workers. They were also among the strongest survivors of the system.

The privileges conferred on the enslaved elite came in several forms: better food, more food, better clothing, more clothing, better and bigger housing, even the prospect (in some rare cases) that a master might use his last will and testament to free them. It could even be demonstrated in a name. For instance, the head driver on one Jamaican sugar estate is listed in the records of 1813-14 by the name of Emanuel, but also by another name: James Reid. The reason for this was that Emanuel had been baptised by an Anglican curate, with the approval of the plantation owner. He was among a minority of enslaved people on the estate with a Christian name and a surname — people whose baptism helped to distinguish them from the multitude. The ledgers are dominated by lists of people identified only by a single diminutive slave name, conferred on them by plantation managers: page after page of Nancys, Marys, Sallys, Junos, Eves, and Venuses; of Toms and Joes, Hectors and Hamlets, Londons and Dublins.

The Anglican Church was one of the pillars of the white establishment in Jamaica, and so being baptised into it conferred prestige. Reid’s owner certainly understood its reinventive power. He wrote in 1783 that “many of the best negroes on almost all estates” were Christened in this manner, “whenever they deserve it”, and he believed this made them “better” slaves (by which he meant harder-working, more loyal). None of this meant that the enslaved elite was being invited to live as the equals of their white masters. Far from it. But slaveholders evidently knew that things such as smarter clothes, superior nutrition, the occasional drink of “port wine”, or even initiation into the rigidly hierarchical Anglican communion could help to diminish the prospect of successful open resistance. This, coupled with the inevitably grisly consequences of a failed rebellion, helped to persuade large numbers of enslaved people to attempt to survive their ordeal by negotiating within the system.

The various privileges extended to the enslaved elite helped to create a conservative attitude among some – keen to protect what they had gained. They also produced an aspirational culture, of sorts, within the slave community – a bleak and tragic shadow of the ‘American dream’ of independence and riches that motivated the slaveholders. Those slaves who lived long enough and were not physically or psychologically broken by plantation work could aim to join the ranks of the skilled, privileged plantation elite. And there is evidence that those who won the favour of white managers and avoided fieldwork cherished those advantages. One slave in Barbados even killed his successor, and then committed suicide when a white manager stripped him of his job as a watchman.

Such stories upset common assumptions about slavery – and about slaves. In the popular imagination and in much historical scholarship, there has been a tendency to perceive enslaved people either as downtrodden victims or as romantic rebels: we often prefer to think of slaves as having been innocent drudges, suffering inescapable torments, or as brave resisters and rebels, taking decisive action against their oppressors. It is a contradictory simplification. The bland confining categories of “victim” or “rebel” (or even “collaborator”) cannot properly capture the experiences or choices of enslaved people, including those of drivers, of enslaved Anglican converts, or of a thwarted Barbadian watchman.

Those people show us, instead, that slavery was as complex as it was cruel. Negotiating its grim realities required determination and skill, even selfishness; and it was next to impossible to endure without making compromises of one kind or other. All enslaved people – from newly trafficked Africans to seasoned field workers; from children forced to work as soon as they could use a small hoe, to experienced drivers such as Reid – responded to their predicaments in ordinary ways, albeit under extraordinary pressures. They did what they could to keep alive and, if possible, to capitalise on scant opportunities within the system in which they were trapped.

And their stories remind us that they were all trapped. However complex and divided the slave community, however many people we find who were able carve out precarious positions of relative comfort, we find them struggling to live within a system designed to promote disunity, anxiety and fear. Even the most valued of drivers could be demoted on a whim. Some brave or desperate souls chose to flee. But the fine-tuned system of divide and rule helped to deter all but the most determined of rebels.

Before the late-18th century, the sophisticated and cruel management strategies of white slaveholders were highly effective: overt challenges to white authority foundered, and slave-run sugar plantations prospered. It was only with the outbreak of the Haitian Revolution in 1791 and the growing influence of humanitarian campaigning that the inner workings of the British slave system began to buckle and break, as enslaved people in the Caribbean seized new opportunities to undermine the world that the slaveholders had made.