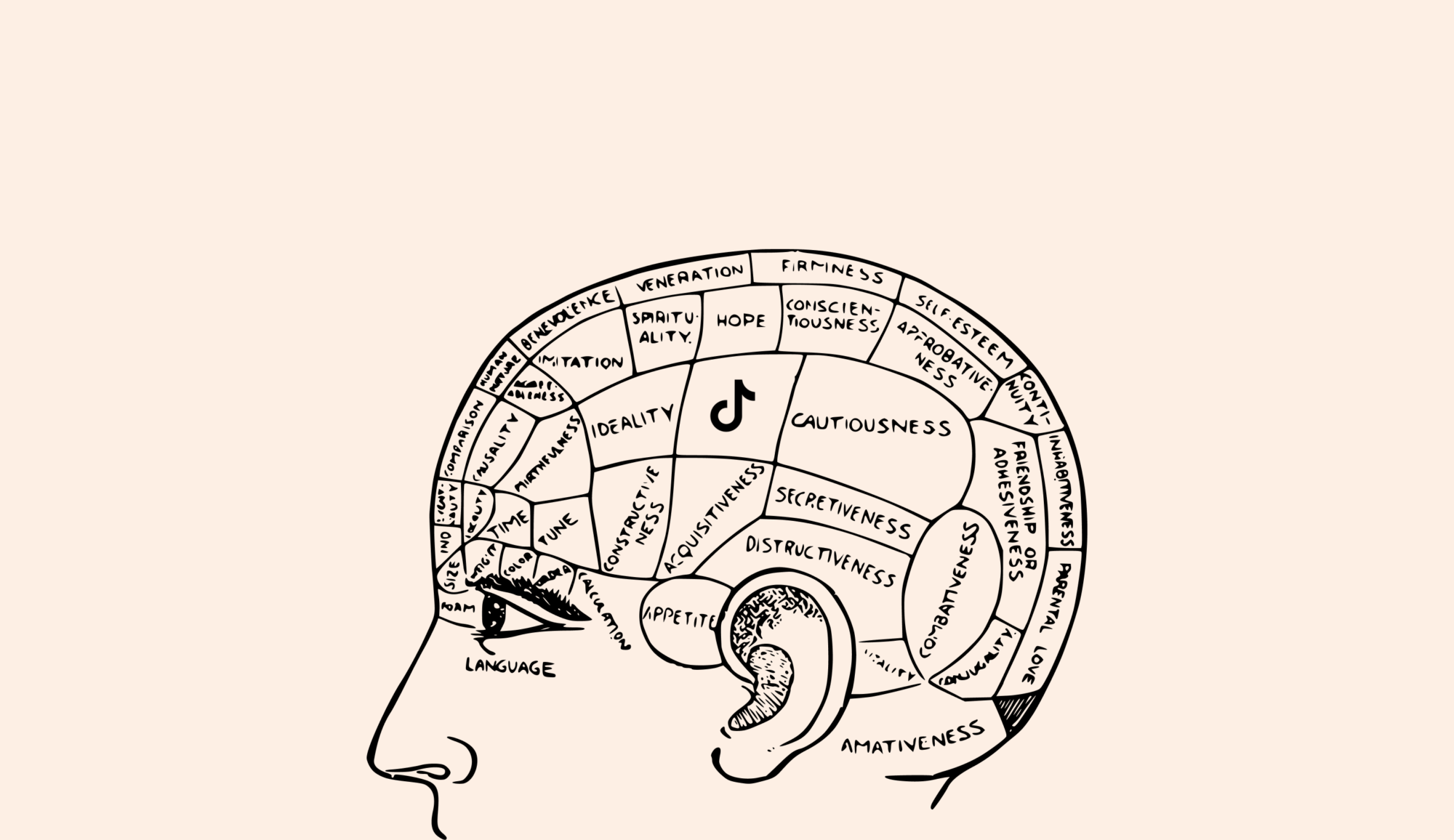

Illustration by Zeyd Anwar; New Politic

I must admit, when I first heard about TikTok I thought the app was for children. Hundreds of lip-syncing videos, alongside dances and make-up tutorials were enough to turn away my attention. But by April 15, 2020 Britain had entered its first lockdown. Looking for some form of entertainment, I caved. I downloaded TikTok and soon became fixated on the never-enduring supply of videos. I had surrendered to the TikTok lockdown craze.

Nor was I alone. In the first quarter of 2020, the beginning of the pandemic, TikTok recorded three hundred and fifteen million installations, the best quarter for any app ever. Isolation related hashtags boomed: words like #quarantine, #safehands and #happyathome all became emblematic of a once in a century pandemic ravaging the globe.

The effects of social media on the human brain have been well-recorded over the past decade. Facebook has been the primary perpetrator: endless news stories of addiction, dopamine spikes, bullying and fake news have hit the headlines, with articles even arguing Facebook has changed society as we know it.

Chamath Paliphapitiya, Facebook’s former vice president of operations, agrees with this assessment. During a talk at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, Paliphapitiya regretted his involvement with the Big Tech giant: “I feel tremendous guilt…I think in the…deep, deep recesses of our minds, we knew something bad could happen…it’s literally at the point now where I think we’ve created tools that are ripping apart the fabric of how society works,” he said. “It’s now time we had a break from some of these tools. The short-term dopamine feedback loops that we have created are destroying how society works. No civil discourse, no cooperation, misinformation, mistruth…we’re in a bad state of affairs.”

Paliphapitiya also berated the short-termism that Facebook propagates: “We curate our lives around this perceived sense of perfection…because we get rewarded in these short-term signals: hearts, likes, thumbs up,” he said. “…We conflate this with value and truth. Instead, what it is, is fake brittle popularity. It’s short term and leaves you even more vacant and empty.”

This begs the question: as a new platform gaining in popularity, is TikTok also changing the human brain? What are the long-term effects of scrolling endlessly and consuming hundreds of videos? Are our brains equipped to deal with this level of stimulation, and is this bad news for us?

The answers to these questions are not positive. TikTok may be shortening our attention spans for the worse.

Although TikTok is fairly new, having launched only in September 2016, the concept of short videos available for bitesize consumption is not. Vine, which began in January 2013, had a similar model. Users were able to create short catchy videos and react to popular accounts within the constraints of six seconds. But TikTok differs, crucially, in two ways: users can record, “duet” and remix content up to one minute, and they can also browse a customised for you page — a default page that tailors and brings content to them, regardless of who they choose to follow.

It is this feature that enables users to find new content and be exposed to a never-ending stream of videos. As users like, comment or scroll, TikTok’s algorithm silently records their preferences. With enough consumption, users can later find themselves with an endless diet of videos tailored to their interests. Jia Tolentino, writing in the New Yorker, neatly summed up the app’s approach to user experience: “Some social algorithms are like bossy waiters: they solicit your preferences and then recommend a menu. TikTok orders your dinner by watching you look at food.”

As I open the app, Tolentino’s description of TikTok could not be closer to the truth. As I open the app, Tolentino’s description of TikTok could not be closer to the truth. Videos of #hustleculture, weightlifting, impersonations, how-to recipes, alongside memes and motivational videos all swamp my for you page. Gone are the videos of lip-syncing and dancing. Of course, the algorithm is not always accurate. But it has largely succeeded in keeping me on the platform for large amounts of time without even noticing. “TikTok’s aim is to keep users scrolling for as long as possible,” a source working in the industry tells me. “That’s how it retains its users.”

TikTok’s impacts are still yet to be conclusively determined, but there are growing signs it is already impacting its users. When TikTok provides us with an endless stream of videos, we become the ultimate judge, jury and executioner. We have three options: we can either exit the app, continue watching the video on the screen, or we can swipe — and keep swiping until we find a video of interest. Stimulation is the goal, and this can take form in various ways. We can find something funny, sad, frightening or happy. Or we can even find it sexual. The point is that we must see something that makes us release enough dopamine, or at the very least, feel something to make us continue watching.

Here lies the problem. As we get used to watching more and more videos, the threshold at which we can continue getting stimulated may be getting higher. When we return to normal media — or even life — we can find it boring, shortening our attention spans in the process.

“When you’re scrolling…sometimes you see a photo or something that’s delightful and it catches your attention,” Dr Julie Albright of the University of Southern California says. “And you get that little dopamine hit in the brain…in the pleasure center of the brain. So, you want to keep scrolling.” Albright then likens TikTok to a Vegas slot machine: “In psychological terms [it’s] called random enforcement. It means sometimes you win, sometimes you lose. And that’s how these platforms are designed…they’re exactly like a slot machine.” Albright continues: “Our brains are changing based on this interaction with digital technologies and one of these is time compression,” she says. “Our attention spans are lowering.”

Scientific research points to this phenomenon. According to research from The Statistic Brain Research Institute, the average human attention span has declined from 12 seconds in the year 2000, to just 8.25 seconds as of the year 2015. A study in Nature Communications, too, has found our collective attention span narrowing.

More than teenagers or millennials, the real victims of this virtual world are children. Although there is no data on the long-term impacts of smart-phones and social media apps like TikTok, there is an emerging volume of literature that indicates these new forms of media could be linked to ADHD and other psychiatric disorders. “The success of human evolution is in part explained by the tremendous plasticity of the human brain,” writes Dimitri Christakis, a paediatrician based in Seattle. “[Plasticity] allows it to be shaped through interactions with its environment. This plasticity, however, also means that early experiences exert considerable influence on neuronal structure, function, and ultimately cognition.”

Since the infant brain is responsive to environmental changes, this raises the concern that excessive stimulation — whether visual or auditory — may lead children to expect an intensity of inputs that, as Dimitri notes, ‘reality cannot provide, thus leading to inattention in later life.” The scientific evidence, however, is mixed. Overstimulation experiments tested in the 1970s found that short-term deficits in attention were results in some, but not others.

Yet the idea that our brains are being trained to respond to shorter and shorter stimuli cannot be far-fetched. Social media first started with Facebook, which involved medium length posts written on a “wall”. Then came Twitter, which encouraged short bursts of information, mainly via “tweets”. Vine and TikTok soon followed, with second long videos. And then so did YouTube and Instagram, both with “shorts” and “reels”. The transition to shorter media is a reflection of how platforms are seeking to maintain and edge in what is now a bitesize content economy. Dr Stephanie Brown, writing in the New York Post, succinctly captures this new form of living: “Society is now dominated by beliefs, attitudes and ways of thinking that elevate the values of impulse, instant gratification and loss of control to first line actions and reactions…in a vicious circle, the exhausting fast pace of life promotes overstimulation and overscheduling, which become chronic stressors that lead to behavioural, mood and attention disorders.”

Societal functioning and human existence have long depended on the ability to plan, work towards goals over a long period of time and opt for deferred gratification. An environment that fosters attention to respond to impulse cannot be conducive to a life that relies on long-term thinking.