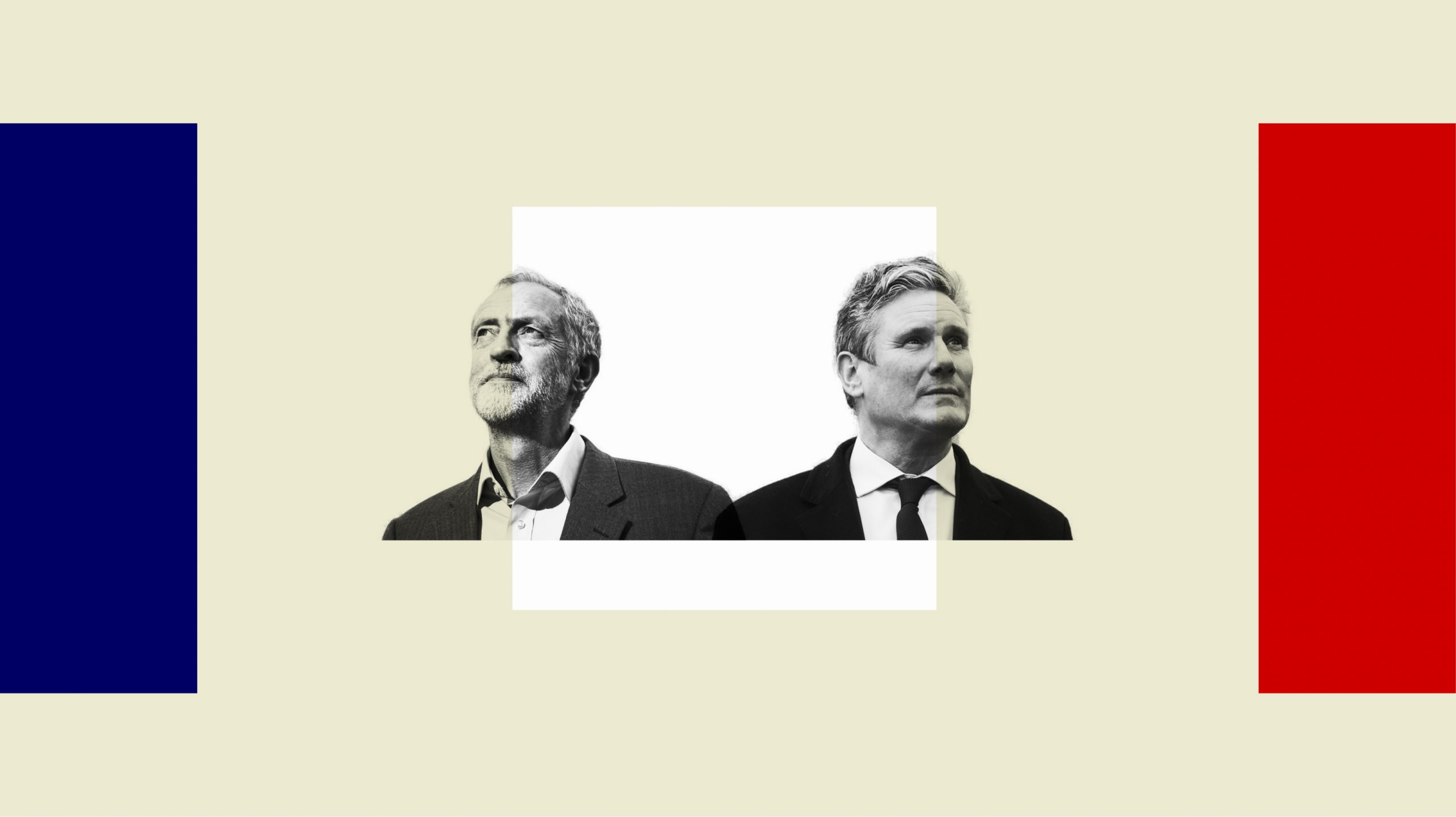

Three things are clear from Keir Starmer’s conference speech: Corbynism is dead and buried; Blairism is making a comeback; and Keir Starmer’s vision for Britain lies in work, care, equality and security. Labour has returned as a serious force for political change, Keir Starmer says, with an eye for power and as a party that the public can trust.

Indeed, Keir Starmer has been clear over his political position over the past seventeen months. He believes the road to electability requires a move to the centre left, that the Left of the party needs to be disenfranchised through rule changes, and the Labour Party needs to operate with more professionalism. What has been less clear is what form this moderate politics entails. After Starmer’s conference speech in Brighton, that question has now been answered: Blairism is back from the dead.

For eleven years, the spectre of New Labour has haunted the Labour Party. Having accepted that the height of the Labour Party’s electoral success came under Tony Blair, the party’s leadership have made peace with Blairism. They now look to it as an ideology that not only needs to return, but one that must be built upon in the years that lie ahead.

Take, for example, Keir Starmer’s hardline position on crime. He claimed that a Labour government would introduce tougher sentences for rapists, domestic abusers and stalkers. In 1995, Tony Blair himself spoke about a Labour government that would be tough on crime, and tough on the causes of crime. Or take Keir Starmer’s commitment to British internationalism, with Britain playing a leading role on the international stage. Tony Blair, through military interventions in Kosovo and Iraq, equally saw Britain as a good force for the world, upholding democracy and the liberal world order. But the most explicit references to New Labour came through praise. Keir Starmer broke away from Ed Miliband and Jeremy Corbyn by commending New Labour’s political record: on the minimum wage, on educational results, on pensions and on poverty. “Education is so important, I’m tempted to say it three times” he said.

Yet there were also elements of Blue Labour scattered through Keir Starmer’s speech. Rather than a focus on “family, faith, flag”, Keir Starmer spoke of “family, faith, work” – a suitable substitution as work slowly becomes the new religion of the 21st century. Claire Ainsley, Keir Starmer’s director of policy, can be credited for this focus. Ainsley’s book, The New Working Class, argues the way ahead for the Labour Party involves using values favoured by the public – family, fairness, hard work and decency. Keir Starmer’s slogan, aside from “Stronger Future Together” is now “work, care, equality and security.”

RECOMMENDED

It’s Keir Starmer’s Time to Lead

by Zeyd Anwar

Tony Blair Wants to Lead the Labour Party Again

by Zeyd Anwar

Labour Must Look to its Opportunities and Beyond its Failures

by Mike Buckley

The aims of this shift are clear. The Labour Party wants to avoid its long held association with idlers and welfare claimants. Instead, the party now values the contribution society – what people put into society, they will get back. People should be rewarded, with security in their jobs, in housing and in their own homes. There is no explicit boss versus worker ideal. Instead, there is a partnership, between the public and the private. “In order to put contribution at the centre of our efforts, Labour would build an effective partnership of state and private sector” a Labour Party press release says, “to prioritise the things that we have seen really matter: health, living conditions, working conditions and the environment.” We all have a role to play, he suggests, with rights and obligations towards each other.

The Labour Party’s Brighton Conference was an opportunity to set forward a different political agenda, but it was also a chance for the leadership to state new values. Keir Starmer decided to begin with the negative. He showed, in essence, that he had made a clean break with Corbynism. At the start of his speech, he welcomed back Louise Elman, the former Labour MP who had left the party over anti-Semitism. “…Louise Elman, welcome home,” he stated to a cheering crowd. The implications were subtle, but clear: I have succeeded where Jeremy Corbyn has failed. And I have held my original promise, which, as he put it in his first speech as leader, was to “tear out [anti-Semitism] by its roots, and judge success by the return to Jewish members [to the Labour Party].

Hecklers also helped Keir Starmer’s cause. They enabled him to bring a contrast between himself and the Left of the party. “Shouting slogans, or changing lives, conference?” Starmer said, with his arms up in the air. His claim that a Labour government would never go into an election without a serious manifesto was again a theme from the days of New Labour: that the Left are only interested slogans, protesting, ideological purity and eternal opposition.

Starmer’s own values emphasised meritocracy and a lifelong commitment to human rights and justice. He pressed on the contrast between himself and Boris Johnson, concluding that he is not a career politician unlike others. “When…I was Chief Prosector working with Doreen Lawrence to…get a prosecution of two of the men who murdered Stephen, Boris Johnson was writing an article in The Telegraph decaring a war on traffic cones. Conference, it’s easy to confort yourself that your opponents are bad people. But I don’t think Boris Johnson is a bad man. I think he is a trival man. I think he’s a showman with nothing left to show.” The line of attack was particularly effective. Rather than attacks on Boris Johnson’s personal character – which have proved ineffective in the past – Keir Starmer was again subtle: in the grand scheme of things, Boris Johnson is trival, since the challenges we face as a country are deeply serious.

The focus on Keir Starmer’s background in the law and justice was also a trick to resonate with voters concerned with crime and anti-social behaviour. The aim was to show Keir Starmer as a leader who can not only take on his own party and be unswayed by pressure, but as a strong politician in his own right who can stand up for British interests. Previous Labour leaders failed this test. Ed Miliband was forced to say whether he was tough enough to take military action during an interview with Jeremy Paxman in 2015, while Jeremy Corbyn was depicted as weak and an enemy of Britain for his commitment to nuclear disarmament, alongside his response to the Salisbury poisonings.

[Read: Tony Blair Wants to Lead the Labour Party Again]

Here, then, was Keir Starmer’s pitch to voters: I am not like other politicians. I have transcended through the class barrier and you can too. You will be rewarded for hard work under a Labour government, in a society where we all contribute and benefit. I am strong, but fair. I am a leader, but also a man of the people.

The overall political substance of Keir Starmer’s speech was nothing new. It was largely a reinstatement of a New Labour style of politics. Not everything, however, was rehashed. His focus on the technological revolution (of which Blair is a strong advocate, and long suggested as a way forward for Labour earlier this year) and climate change were welcomed differences. But it was still difficult to see the overarching policy, theme or political idea. The speech felt scattered with various announcements.

Keir Starmer’s execution was also problematic. Jokes, pauses and body language felt forced. A remaining challenge for Keir Starmer is how he can develop his charisma and relate to the public. As one MP who lost their seat in 2019 put it, “The challenge is not to lay out what he believes in academic terms, but to establish an emotional connection. A kind of Prescott punch, really.”

Importantly, we know also know on what terms the next election will be fought, at least on tax and fiscal policies. Dead are the old political rules, where the Labour Party argues for higher taxes and greater spending, and the Conservative Party proposes lower taxation and a smaller state. Instead, Keir Starmer will pivot and focus on he fairness of taxation, who is carrying the burden of taxation, and its value for money. The fiscal arguments, meanwhile, will shift to green borrowing for a fair and heavy net zero transition, while the Conservatives focus on reducing a pandemic deficit.

For months, critics and supporters of Keir Starmer have waited to hear where he stands of policy and politics. Although many policies are yet to be announced, one thing is is now clear: New Labour is back, and it’s ready to govern once again.