Sugar cane cutters in Jamaica

This article is part of Project Empire, an editorial series designed to explore the history of the British Empire. See the full collection here »

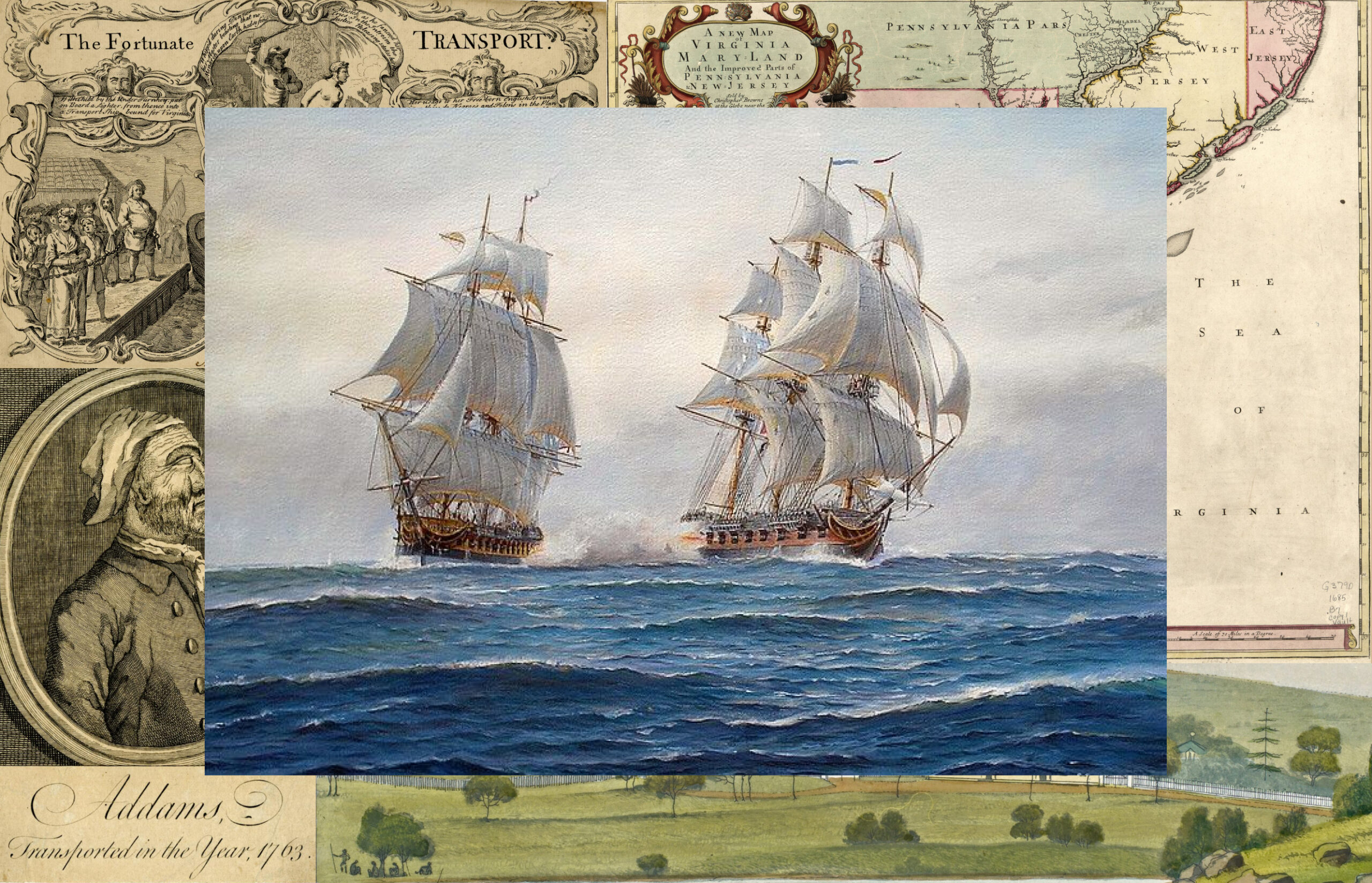

One of the biggest controversies in the current historiography of race and slavery in American history is the New York Times-inspired 1619 Project. Much of the findings of the 1619 Project seems to me unexceptional, even if these findings — notably that American history should be reoriented around the history of slavery rather than the history of freedom — have riled numerous Americans who prefer other histories of their nation. It is a truism among historians that race is the most divisive issue in American history and that the origins of racial difference preceded the creation of the United States of America. These ideas about racial difference, with whiteness seen as more important than blackness, emerged during the 169 years of British rule over European-settled regions of North America, at the time the land of the British empire.

It was in these years that slavery was introduced; when the economically successful and exploitative plantation system, based on the labour of enslaved Africans, was perfected. North America also saw the importation of thousands of West Africans into the American South, all to labour as enslaved workers, just as their children and grandchildren before them. In the eighteenth century, the British empire in the Americas was firmly based upon slavery. As Barbara Solow argued, “it was slavery that made the empty lands of the western hemisphere valuable producers of commodities and valuable markets for Europe and North America. What moved in the Atlantic during these centuries were predominantly slaves: the output of slaves, the input of slave societies, and the goods and services purchased with the earnings of slave products.”

Slavery was, along with the dispossession of Native Americans from their lands, central to the history of colonial British North America. It was even more important to the imperial story once the sugar producing powerhouses of the British Caribbean — where over ninety percent of the population was brutally exploited as enslaved workers — are included in any analysis. Recent estimates suggest that preceding the American Revolution in 1776, six percent of the British economy depended upon the slave trade and the plantation produce exported to Britain. That is large, if not overwhelming — equivalent today, perhaps, to what the computer industry accounts for in the modern British economy.

It is no surprise, therefore, that the plantation sector was universally supported in Britain. The planters whose wealth was firmly based upon the labour of enslaved Africans had a disproportionate influence on British politics. William Pitt the Elder, whose closest ally was the wealthy Lord Mayor of London and Jamaican planter William Beckford, owned 1,356 slaves. He once declared that sugar planters be thought of in the same way “as the landed interest of this kingdom.” It was a “barbarism to consider them otherwise.”

It is for this reason that any historian of mid-eighteenth-century slavery in the British Caribbean would find the contention made in the 1619 Project perplexing. It is that the founding fathers, like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, rebelled against Britain as a pre-emptive strike, since they believed that Britain was becoming an antislavery nation, preparing the way to abolish slavery in its empire. “Conveniently left out of our founding mythology is the fact that one of the primary reasons some of the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery,” writes Nikole Hannah Jones, founder of the 1619 Project. “In other words, we [America] may never have revolted against Britain if some of the founders had not understood that slavery empowered them to do so; nor if they had not believed that independence was required in order to ensure that slavery would continue.”

It is a strange argument, and one that ignores the fact that the centre of slavery in the British empire was the Caribbean. It contradicts not only how committed the British empire was to slavery in the 1770s and how far it was from being an antislavery nation in 1776, but how vicious the slavery regime practiced by British colonists in the West Indies was. The 1619 Project suggests that the British empire was gentle and righteous on slavery compared to the revolutionaries who founded the United States. This interpretation flounders as soon as we examine West Indian slavery during the eighteenth century.

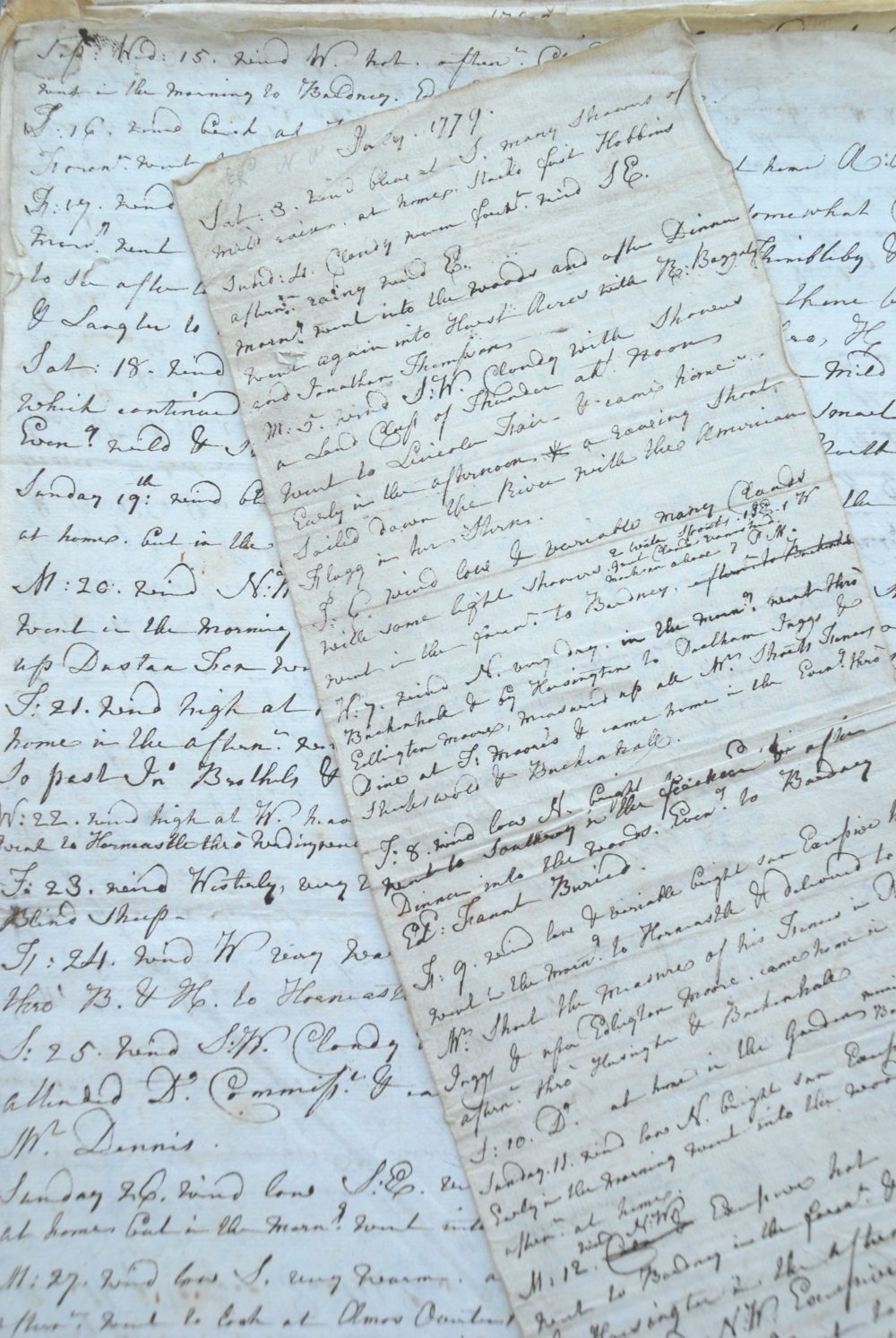

Richard Dunn, a distinguished historian who compared slavery in Jamaica and Virginia, claimed that “Caribbean slavery was one of the most dehumanizing systems ever devised.” My Book, Mastery, Tyranny, and Desire; Thomas Thistlewood and His Slaves in the Anglo-Jamaican World confirmed that Dunn was right. Thomas Thistlewood was a Lincolnshire-born migrant, who lived in western Jamaica between 1750-1786. His diaries revealed, in devastating detail, the brutality experienced by Jamaican slaves in the third quarter of the eighteenth century.

The brutality of slavery was exhibited in numerous ways: it was seen in the relentless sexual exploitation of enslaved women; in the numbing frequency of sadistic whippings and humiliations; and in the frequent acts of suicide by the enslaved, many of whom were driven to despair. No woman was safe from Thomas Thistlewood on the plantation or small farm he managed. During his time as a master, Thistlewood raped hundreds of female and underaged slaves. Many slaves felt the only option left was suicide. In 1756, a slave named Moll was recorded to have drowned herself “wilfully”, while the slaves who declared they wanted to die — as another slave called Nero did in 1754 when he “Would not Work, but threatene’d to Cutt his own throat,” — were punished by Thistlewood. Thistlewood noted that he had Nero “Whipp’d, gagg’d, & his hands tied behind him so that the Mosskitoes and Sandflies might torment him to some Purpose.”

Excerpts from Thistlewood’s diary / Thomas Thistlewood archives

Unsurprisingly, many slaves tried to escape their predicament. In the 1750s, slaves ran away from Thistlewood on a regular basis, as much as one every week in 1756. Occasionally, the enslaved fought back. In 1760, Thistlewood experienced the largest slave revolt yet seen in the Caribbean: that of Tacky’s Revolt. The rightful leader of the rebellion, a West African chieftain called Wager, sold into slavery on a large sugar plantation, was the orchestrator of the rebellion. His rebellion nearly succeeded, giving the white rulers of Jamaica an existential shock, but determined action by the Jamaican governor, Henry Moore, along with the deployment of British troops, Jamaican militia, and Maroons (autonomous bands of people of African descent living in the Jamaican interior) led to his defeat. Wager faced a gruesome death: he was placed in a gibbet, or a cage, where he was held until he died from starvation.

The examples of ill-treatment and degradation meted out to the enslaved in this period were endless. Yet what made the British slave system in the Caribbean especially chilling was the systematic manner in which slaves were overworked, underfed and routinely neglected. Such attributes were a structural part of a system devised by white planters to maximise their profits. White planters and slave merchants were the richest people in the British empire; they lived lavishly and indeed extravagantly. Their enslaved property, however, had the lowest standards of living of any people so far studied in the pre-modern period. The enslaved produced income on average of £16 per person for their owners. In return, they were given inadequate food, clothing and housing worth not much more than £3 or £4 per annum. When drought, hurricane or war made conditions difficult, the enslaved starved to death.

Enslaved women were also some of the most unfortunate. Female slaves worked more than men in the fields of sugar, digging cane holes, harvesting sugar cane and operating the boiling houses. They were equally discouraged from having children. If they did have children, they continued to work until late in their pregnancies, and returned to work soon after their children were born. The result was a high infant mortality rate and foreshortened female life expectancy. Slave populations inevitably failed to thrive. It was only through a substantial slave trade that planters kept their fields supplied with new labour, making up through the vicious slave trade for an average annual decline in the enslaved population of three to four percent per annum.

Planters liked to pretend they were humane and that they had the interests of their enslaved people at heart. In Jamaica, the opposite was true. The wildly successful Atlantic slave trade brought thousands of fresh labourers to the island and reinforced short-termism among the plantocracy. The principal ambition was to create the largest possible number of crops in return for healthy profits. It was a ferociously hard-driving system, one that operated on just-in-time principles. It also involved the subcontracting of the toughest work to “jobbing gangs” (“jobbers” were men, usually without land, who owned gangs of enslaved people. These gangs were often contracted by planters to do difficult work, work that the planters did not want their own slaves to undertake). The enslaved not only had to work beyond endurance in growing sugar, they had to feed and house themselves. This system worked if the enslaved was able bodied and had few dependents. It was disastrous for the numerous enslaved who suffered ill-health or had children.

Poor work, overwork, constant punishment and continuing sexual exploitation of enslaved women, along with the pressures of short-term profit maximisation drove many enslaved people to desperation. One especially honest and forthright slave manager, William Fitzmaurice, declared before the House of Commons that when he remonstrated with newly enslaved people that they should stop dirt-eating (a common affliction among the enslaved), they told him “constantly” that they “preferred dying to living.”

The ideas therefore put forward in the 1619 Project that the British empire was benevolent towards the enslaved compared to America — and that Britons were inclined towards abolition as early as the 1770s — are demonstrably false. If slaveowners wanted their rights protected over their enslaved property, this protection came best from the British Empire, one of the chief beneficiaries of the most brutal slave system in existence. It is true that the United States was founded by slave owners and was a pro-slavery nation at its conception. Nevertheless, to posit the idea of Americans as bad and British imperialists as good is not just simplistic, but is a false and misleading dichotomy.

Thomas Thistlewood died in his bed aged sixty-five in 1786. His misdeeds towards the people he held in miserable bondage were typical of imperial subjects, in a time when Britain found no qualms with a system that satisfied their sweet tooth. Centuries later, we still yet have to reckon with how British subjects treated enslaved Africans in its eighteenth century-empire.