Behind The Lens

Profiles

PROJECT EMPIRE

How the English Language Conquered the World

This article is part of Project Empire, an editorial series designed to explore the history of the British Empire. See the full collection here » In 1170, Richard De Clare, the English Earl of Pembroke, subdued the Irish city of…

The Criminal Origins of the United States of America

Illustration by Zeyd Anwar; Credits: Wikipedia; British Library; British Museum This article is part of Project Empire, an editorial series designed to explore the history of the British Empire. See the full collection here » On December 15, 1722, twenty-seven…

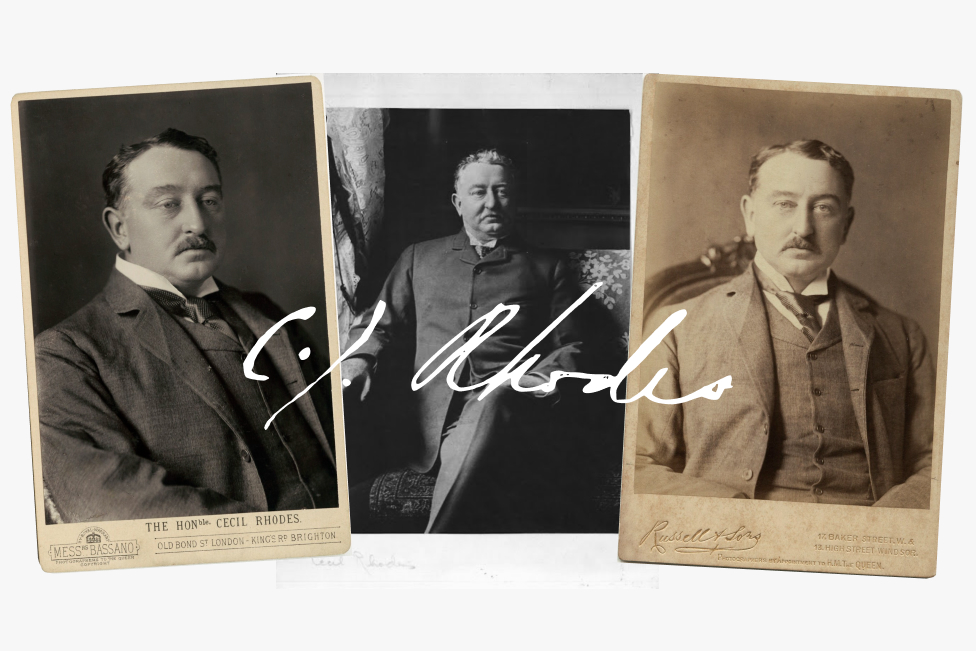

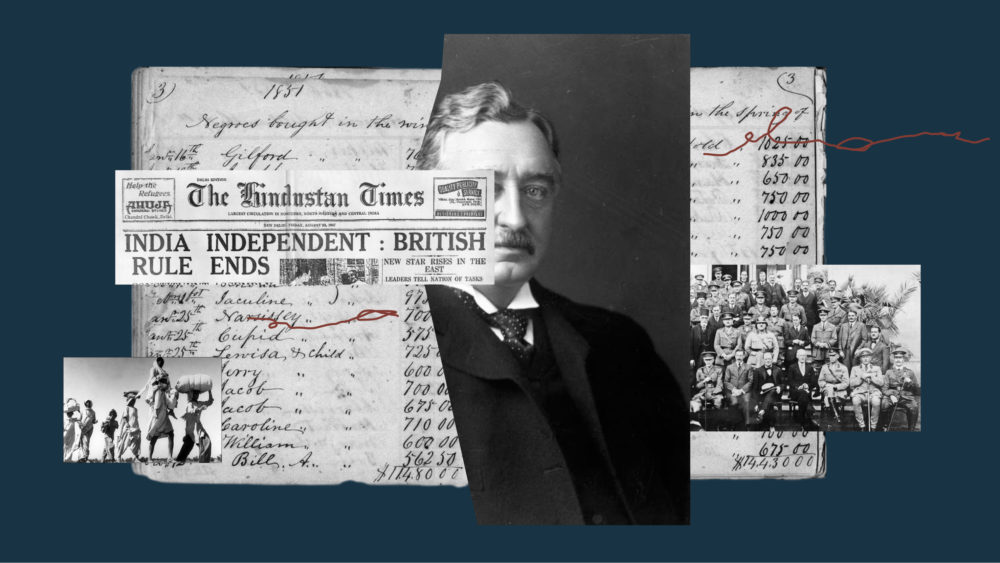

The Real Cecil Rhodes

This article is part of Project Empire, an editorial series designed to explore the history of the British Empire. See the full collection here » I doubt many of us would feel comfortable putting up a statue with the following…

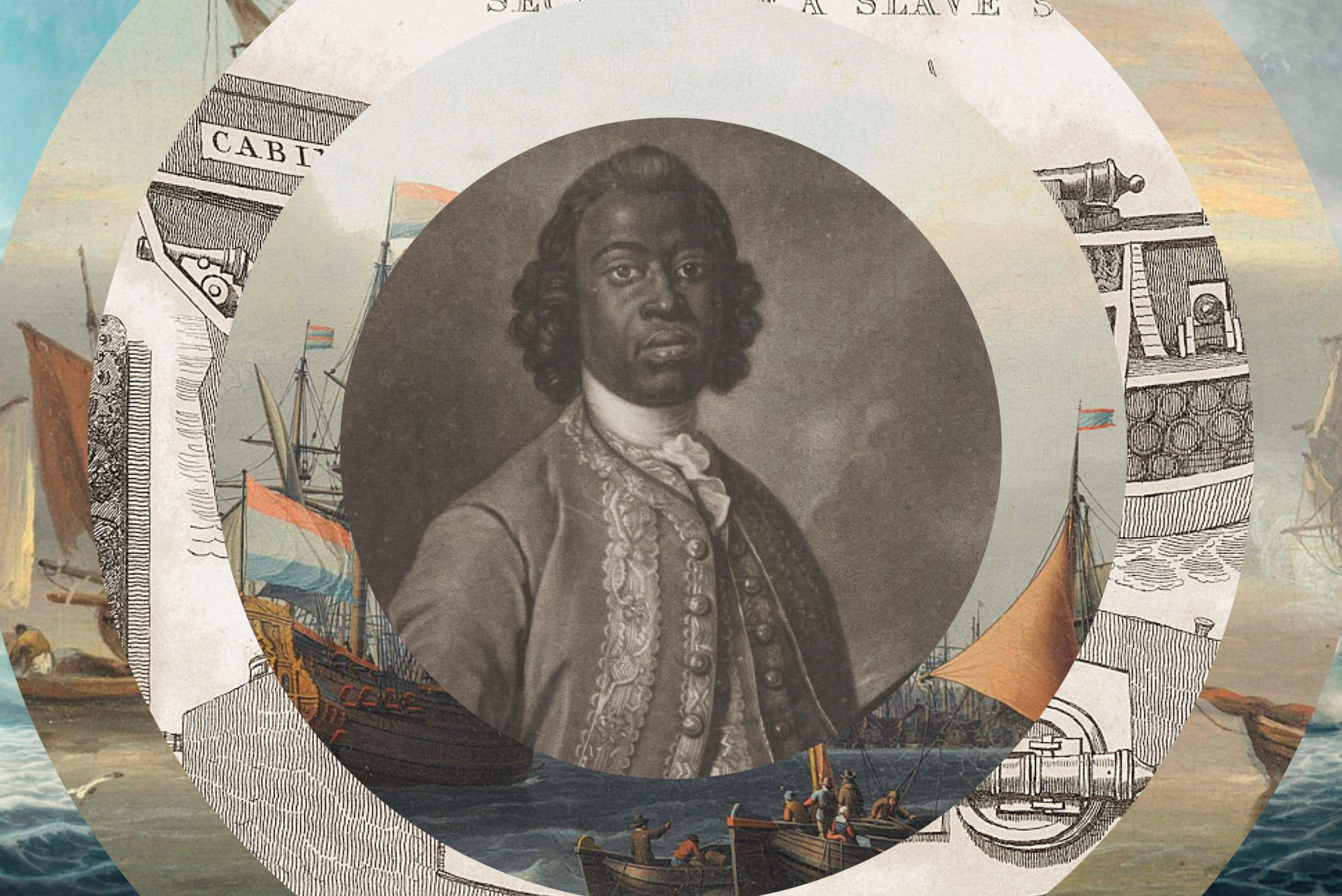

The Enslaved Prince of Annamaboe

Illustration by Zeyd Anwar; New Politic; National Portrait Gallery; Christies This article is part of Project Empire, an editorial series designed to explore the history of the British Empire. See the full collection here » The entrance door to the…

Introducing Project Empire

Illustration by Zeyd Anwar; New Politic This article is part of Project Empire, an editorial series designed to explore the history of the British Empire. See the full collection here » Lives were taken and millions were displaced. Countries were…

The Internet Dictionary

Latest Posts

안전한 카지노 사이트 및 바카라 사이트

안전한 카지노 사이트 및 바카라 사이트 안전한 카지노 사이트 및 바카라 사이트 길잡이 : 한국에는 많은 온라인 카지노 사이트 및 바카라 사이트가 존재 합니다. 너무 많은 곳이 생겨나고 없어지기에 규제를 하더라도 쉽지 않은 상태 입니다. 온라인에서 떠도는 여러 사실들은 진실인지 거짓인지 파악하기도 어렵습니다. 이…

The Internet Dictionary What Does TYSM Mean?

New Politic What is the meaning of TYSM? TYSM is an acronym which stands for “thank you so much”, a common expression of gratitude. However, it’s not always a sincere expression — it can also be used sarcastically. It’s most…

The Internet Dictionary What Does 1437 Mean?

Flickr It turns out that the rather random date 1437 actually translates to a much more sentimental expression than what meets the eye: I love you forever. Translating 1437 You’re probably wondering, how does that work? It’s actually to do…

The Internet Dictionary What Does FT Mean?

Louis Abate / Flickr Like many of the abbreviations The Internet Dictionary covers, there is no single universal meaning to the term “FT”. But here are the three most common uses of the term, so you can be confident that…

The Internet Dictionary What Does IMY Mean?

Megan Stallings / Unsplash What does IMY mean? “IMY” is an initialism which stands for “I miss you.” To miss someone is to feel sad or sorrow that a specific person is not present or with you. However, note that…

Who is Victoria Starmer, Keir Starmers Wife?

Victoria Starmer and Keir Starmer at the Labour Party’s Brighton Conference, September 2021 Victoria Starmer remains something of a mystery. Unlike Carrie Symonds, Victoria Starmer has shunned the limelight, deciding to stay quiet about her private life while her husband…

The Internet Dictionary What Does Neek Mean?

New Politic What is a Neek? A neek is someone who studies a lot, is an intellectual or gets good grades, spends little time socialising and has a low social status. The term isn’t particularly hurtful (especially compared to other…

The Internet Dictionary What Does To No Avail Mean?

The idiom “to no avail” is another way of saying some act was unsuccessful or ineffective as it did not achieve the desired outcome. In other words, it is a softer and more subtle way of implying failure. Usually, the intended…

The Internet Dictionary What Does SNM Mean?

Kristina Flour; Unsplash What does SNM mean? SNM is an acronym which means “say no more”. It’s used in a conversation to tell someone that you have a complete understanding of a particular topic or situation — and nothing else…

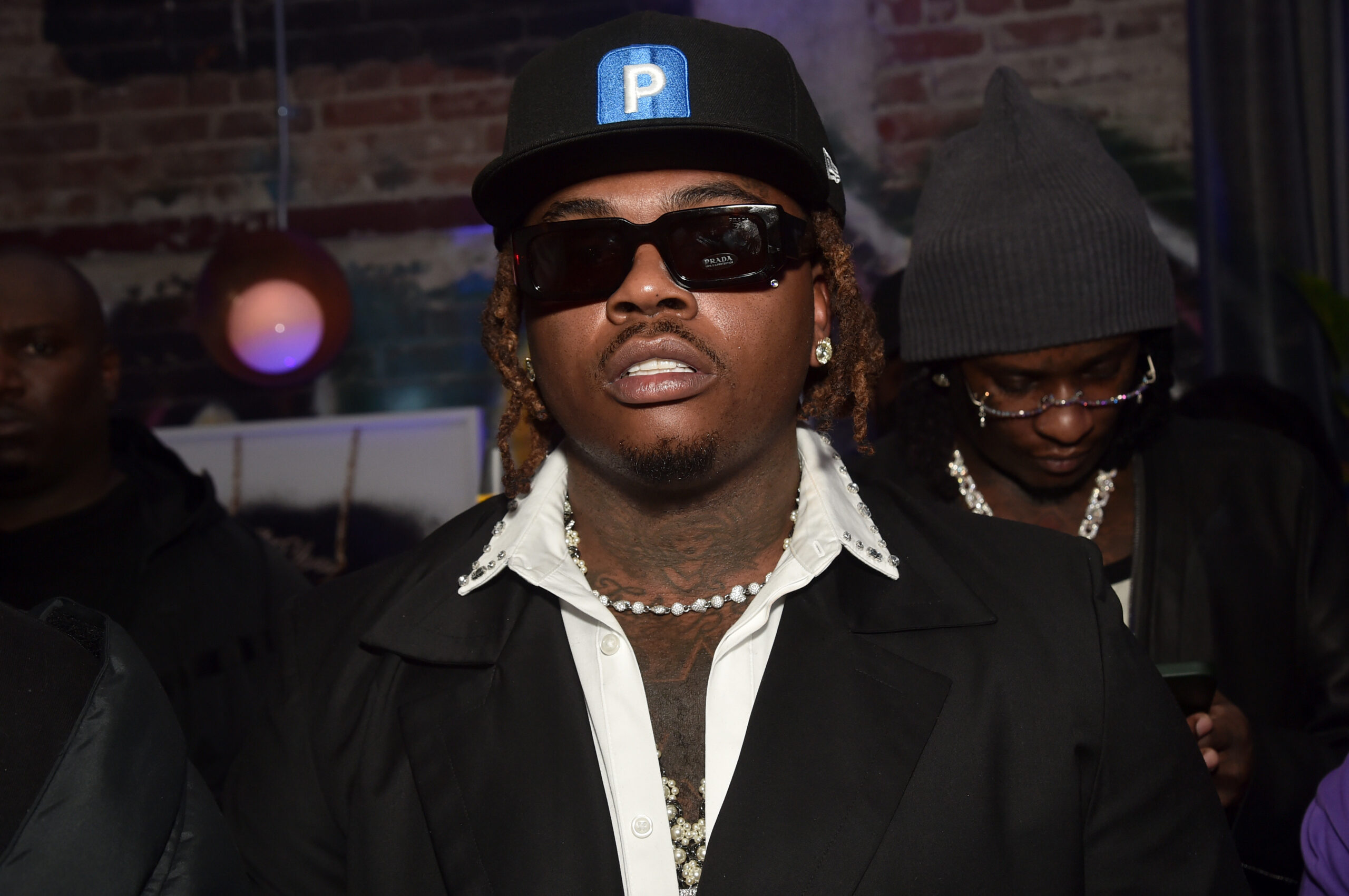

The Internet Dictionary What Does Pushing P Mean?

Gunna, known in real life as Sergio Giavanni Kitchens “Pushin’ P Yeah, pushin’ P, turn me up Turn me up, P, uh-ah” The lyrics from American rappers Future and Gunna’s song, pushin P, released in early 2022 have taken the…